Abstract

The environmental impact assessment in Malaysia can generally be categorized as preliminary and detailed. Public participation in preliminary EIA is confined to the review of environmental impact statements by technical committees. Public participation in detailed EIA is more extensive involving inputs of ad-hoc panel members during scoping, public display and comments of EIS as well as review of the EIS by the panel members. Consultation with affected communities is conducted by consultants during EIS preparation though the process is not spelled in the legislation. At only the initial level of involvement in the spectrum of public participation, there is still much room for improvement in engaging the public in the Malaysia EIA. Public participation in the Malaysian EIA could be extended beyond the EIS review stage by engaging the public in scoping and assessment and even during development of policies and plans. Public participation in Malaysia requires further facilitation to improve accessibility to the necessary information for effective provision of comments.

Keywords

Public participation, consultation, EIA, EIS, Environment, Malaysia

Introduction

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) is a process to systematically identify, predict, evaluate and mitigate impacts of development proposals to facilitate decision-making by relevant authorities on the worthiness of the proposals. The impacts evaluated consist mainly of the biological, physical and social aspects [1]. The EIA has its origin in the United States (US) with the enactment of the National Environment Policy Act (NEPA) in 1970. The act was developed in response to mounting public awareness for environmental protection stemming from increasing pollution across the US due to industrialization and urbanization [2]. The Santa Barbara oil spill in 1969 and construction of the Interstate Highway System resulting in extensive losses of ecosystems both pushed for the subsequent passing of NEPA [3]. Since then, other countries began to model their environmental laws after NEPA and to date, there are more than 100 countries in the list [4].

Only 4 years later, the Environmental Quality Act 1974 was enacted in Malaysia requiring development proposals with significant environmental impacts to have EIA conducted under Section 34A [5]. However, it was until 1987 that the Environmental Quality (Prescribed Activities) (Environmental Impact Assessment) Order was made and the order came into effect on the 1st April 1988. While prescribed activities had not been well defined under Section 34A of the Environmental Quality Act 1974, thus limiting the ability of the Act to dictate EIA for certain proposals, it became clear in 1988 that the prescribed activities listed in the Order would be subject to EIA [6]. The order was replaced by the Environmental Quality (Prescribed Activities) (Environmental Impact Assessment) Order 2015 [7]. The major difference of the two Orders, other than a revision of the prescribed activities, is that the 2015 version specifies the prescribed activities whose environmental impact statements (EIS) require public display and comments. Both the Orders do not illustrate the EIA process and the process is not easily accessible on the official portal of the Malaysian Department of Environment [6, 7].

EIA Process in Malaysia and Public Participation

There are two types of EIA, namely the preliminary and detailed EIAs. The types of EIA have not been stated in the Orders but have been mentioned in the guide for investors published by DOE [6-8]. Prescribed activities listed in the First Schedule of the Environmental Quality (Prescribed Activities) (Environmental Impact Assessment) Order 2015 do require to have the EIS public displayed and commented, and are generally subject to the preliminary EIA. However, those listed in the Second Schedule of the Order prompting public display and comments of the EIS are put through the detailed process [7, 8]. Prescribed activities in the Second Schedule are deemed to have larger impacts than those in the First Schedule due to comparatively larger scale of the activities. Both the preliminary and detailed EIAs undergo the typical EIA stages of screening, scoping, EIS preparation and review, decision-making and follow-up but the stages differ in levels of details and activities [9]. A comparison of both the processes is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of Preliminary and Detailed EIAs in Malaysia.

|

EIA Stage |

Preliminary EIA |

Detailed EIA |

|

Screening |

Prescribed activities in the First Schedule of the EIA Order 2015 |

Prescribed activities in the Second Schedule of the EIA Order 2015 |

|

Scoping |

Terms of Reference (TOR) is submitted to the state DOE office. The scope of EIS is confirmed through issuance of a formal letter by the office.

|

TOR is submitted to the national DOE headquarters. DOE calls for ad-hoc panel meeting for the TOR at the headquarters. The ad-hoc panel comprises government officers, academics of universities and representatives of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). If additional scope is required, the TOR is then revised and resubmitted. |

|

EIS Preparation |

Preparation of preliminary EIS based on the scope stated in the letter issued by the state DOE. No public display and comment of EIS is required. |

Preparation of detailed EIS based on the scope in the final TOR submitted. Copies of EIS are displayed at locations specified by the DOE, including the state DOE offices, the headquarters, universities and public libraries for public comments. |

|

EIS review |

EIS is distributed to technical committee members for review. The technical committee usually comprises government officers. Technical committee meeting is held at the state DOE office for evaluation of whether the EIS meets the legal requirement and addresses all relevant impacts satisfactorily. |

EIS is distributed to ad-hoc panel members for review. Ad-hoc panel meeting is held at the DOE headquarters for evaluation of whether the EIS meets the legal requirement and addresses all relevant impacts satisfactorily. |

|

Decision-making |

The state DOE director approves or rejects the EIS or requires provision of additional information before approval. If approval is granted, it comes with a set of approval conditions. |

The Director General of DOE approves or rejects the EIS or requires provision of additional information before approval. If approval is granted, it comes with a set of approval conditions. |

|

Follow-up |

Post-EIA monitoring which involves submission of quarterly environmental monitoring reports to the DOE. |

Post-EIA monitoring which involves submission of quarterly environmental monitoring reports to the DOE. |

From Table 1, it appears that only detailed EIA involves public participation. To understand the extent of public participation in Malaysia, a further probe of the definition of public participation and the definition of public is necessary. The IAIA defines public participation as ‘involvement of individuals and groups that are positively or negatively affected by, or that are interested in, a proposed project, program, plan or policy that is subject to decision-making process” [10]. The undertakings of public participation implies the democratic approach of a country [11]. For instance, a deliberative approach provides limited means for the undertaking of public participation in comparison to the collaborative approach which upholds inclusiveness, openness and consideration of multiple perspectives for effective planning and decision-making [12]. Lawrence perceived EIA as a form of social learning in the quest for sustainable development during which all stakeholders have the opportunity to enhance their knowledge [13].

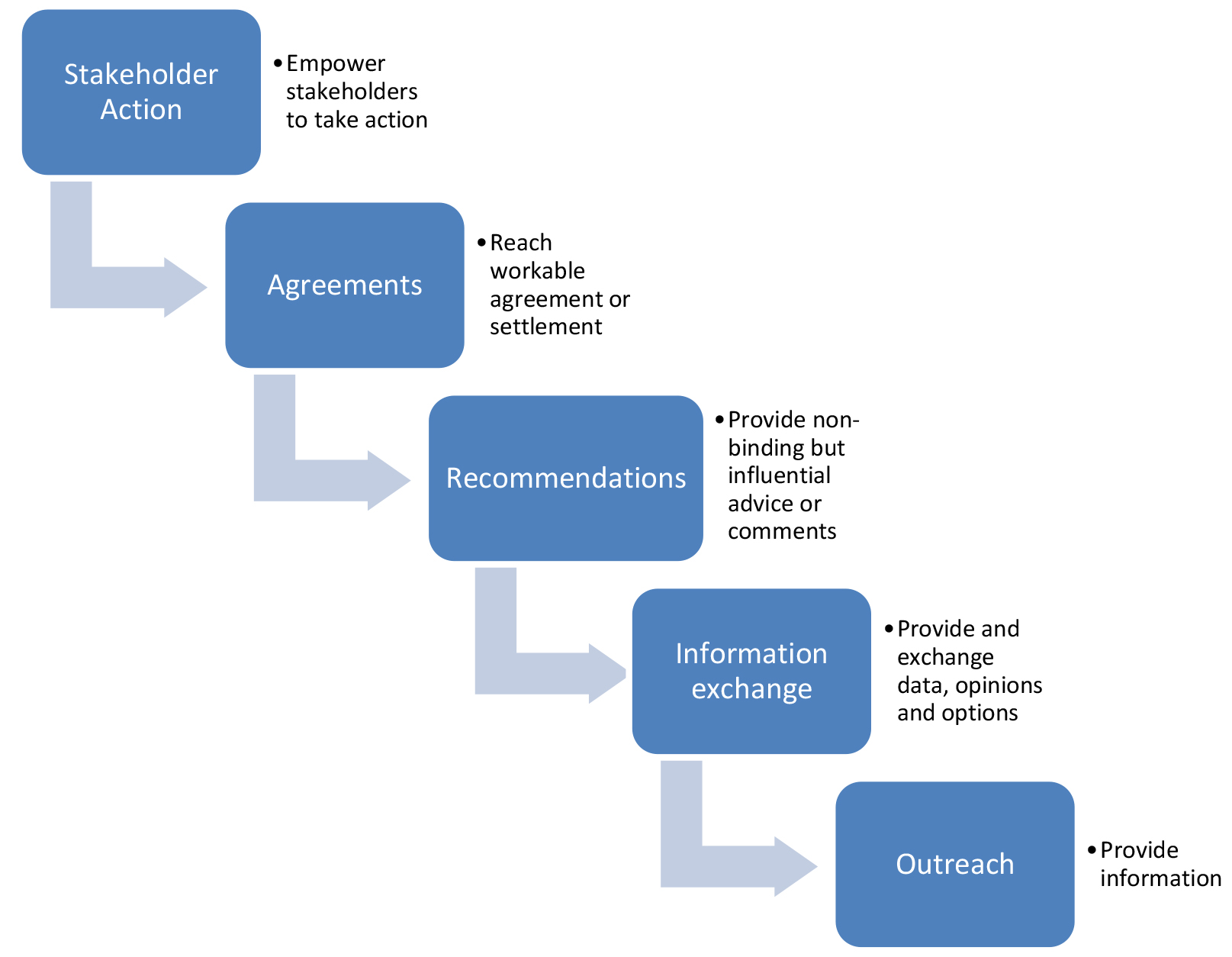

Participation is fundamentally different from consultation in the sense that participation involves active engagement in decision-making while consultation is confined to the request of information and inputs from intended parties [14].Putting participation on a scale, consultation can be visualized as a lower level of participation providing minimum opportunity for the public to be involved in decision-making [15]. The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) divides public participation into 5 levels starting with informing at the bottom which revolves around provision of unbiased information to the public so that they can understand the issues at hand. Consultation is at the next level up. Involvement sits higher that consultation and focuses on engagement with the public to ensure public needs and concerns are continuously gathered and considered. Next on the spectrum is collaboration which forges a partnership with the public in identification of alternatives and solutions. The highest level is empowerment which grants the decision-making power to the public [15]. The EPA’s spectrum of public involvement aligns with that of IAP2 in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Spectrum of Public Involvement [16].

The Level of Public Participation in the Malaysian EIA

Referring again to Table 1, elements of public participation can now be identified in both the preliminary and detailed EIA processes. In preliminary EIA, it is confined to the review stage involving stakeholders in the technical committee who comprise largely of government officers. In detailed EIA, public participation is garnered via public display and comments of the EIS at designated locations as well as the review of the TOR and the EIS by ad-hoc panel members consisting of government officers, academics of universities and representatives of NGOs.

There is minimal involvement of other members of the public particularly those affected by the proposals in preliminary EIA as reflected by the process in Table 1. In practice, consultants appointed to prepare the EIS may conduct social survey to gather opinions of the communities around the project area but such practice widely varies as it is not required in preliminary EIA, hence a lack of model to be adopted [8, 17]. For detailed EIA, there is a higher extent of public participation starting from the review and comments of the TOR by the ad-hoc panel members to the review of the EIS by the members. Public participation has also been extended to the public display of EIS at designated locations for comments and announcement of the display via DOE’s website and newspapers. This is akin to the level of involvement of the public participation spectrum proposed by IAP2 and the level of recommendation in the EPA’s spectrum. Public display of EIS invites comments not only from those affected by the proposal but other members of the public whom are concerned about the proposal [17].

At this point, it becomes clear that public participation in Malaysia is often confined to particular stages of EIA for instance, the EIS preparation and review stages of preliminary EIA if social survey is conducted during impact assessment. Based on Wood’s model of EIA [9], public participation should permeate every stage of EIA starting from consideration of alternatives to monitoring action impacts. Nonetheless, different countries may incorporate public participation to varying extents at different stages of the EIA. Taking the Western Australia for example, public comments are invited during screening on the need for assessment and the level of assessment of a proposal. This extends to the scoping stage with publication of the Environmental Scoping Document, equivalent to the TOR in Malaysia on the website of the environmental authority for public comments. The EIS is also published for comments and the final decision on EIS approval can be appealed [18]. In New Zealand, while there is no public scoping, public participation is facilitated via public hearing and review of EIS. For public hearing to be held, it must either be requested by members of the public who have provided comment on a proposal or come under the decision of the ministry or environmental agency. Nonetheless, public participation in New Zealand is not confined to EIA [19]. The Resource Management Act 1991promotes public participation via open standing at the stage of national policies and plans establishment and application by members of the public to Environmental Court for enforcement order in pursuit of sustainable management. At regional level, consultation with Tangata Whenua i.e. the local Maori people is conducted for development of regional and district plans [20].

In Malaysia, based on the author’s experience in environmental consultation, public meetings are conducted for detailed EIA involving the communities at the vicinity of the proposed development sites and such meetings are usually conducted once or twice to gather their inputs and perceptions of the proposals. Certain concerns are addressed by the proponents during the meetings but follow-up of the inputs, comments and perceptions via a feedback mechanism is lacking. Such approach is at best a form of consultation. The affected communities have very little influence over the alternatives of the proposal unlike in the Western Australia where public comments are invited from the screening stage of EIA and in New Zealand, where public participation comes even earlier at the strategic assessment stage [20, 21]. The public display and comments of EIS at designated locations can be perceived as involvement or recommendation level engaging the general public and not just the affected communities in providing concerns. The practice, however, is not well-facilitated. The availability of EIS at specific locations limits the accessibility of the public to the information necessary to provide their comments. The public can also purchase the EIS from the appointed EIA consultant at a cost which is often quite prohibitive [22]. This forms a stark difference to Western Australia where information related to the EIA ranging from scoping documents, EIS to assessment of the authority and final approval are posted on the website of the environmental authority [21]. In New Zealand, the EIS are also readily available online for public comments and only commercially confidential information is withheld [23]. A search on the World Wide Web reveals very few complete EIS of proposals in Malaysia and in most instances, only the executive summaries are made available.

The EIA process may differ in states in Malaysia having their own environmental legislation and it appears that public participation could elude the state’s EIA legislation [24]. Other than engagement of government officers and NGOs in the review of EIS, public participation could be missing from the EIA process and the access of EIS could be made tedious, thus further hampering public engagement in EIA.

Conclusion

Public participation has been incorporated into the EIA processes in Malaysia but it is still far from maturity. The most common form of public participation is consultation involving representatives of government departments and NGOs in the review of EIS. For detailed EIA, the extent of public participation is increased with public display of EIS for comments and the review of TOR by ad-hoc panel members as well as their inputs during scoping meeting. However, general members of the public have not been actively engaged in the EIA processes. It can be argued that the knowledge level of the Malaysian public members in providing constructive comments is still relatively low [17]. However, in a democratic system, it is the right of the public to have access to the necessary information to provide their thoughts and feedback, and such right should be respected in decision-making. Besides, public participation in EIA should be viewed as a form of social learning through which higher level of public knowledge in this respect can be achieved. It is therefore recommended that public participation in Malaysia should be extended beyond the EIS review stage and should be facilitated by making necessary information available on an official online portal.

References

- MacKinnon AJ, Duinker PN, Walker TR (2018) The Application of Science in Environmental Impact Assessment. United Kingdom: Routledge 2018.

- Rychlak RJ, Case DW (2010) Environmental Law: Oceana›s Legal Almanac Series. New York: Oxford University Press 2010: 111–120.

- Mohl RA (2007) Stop the road: Freeway revolts in American cities. J Urban Hist 2007 July 01.

- Eccleston CH (2008) NEPA and Environmental Planning: Tools, Techniques, and Approaches for Practitioners. Fluoride. US: CRC Press 2008.

- https://www.doe.gov.my/portalv1/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Environmental_Quality_Act_1974_-_ACT_127.pdf

- http://www.doe.gov.my/eia/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Environmental-Quality-Prescribed-Activities.pdf

- https://www.doe.gov.my/portalv1/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Perintah-Kualiti-Alam-Sekeliling-Aktiviti-Yang-Ditetapkan-Eia-2015.pdf

- Environmental requirements: A guide for investor. Putrajaya, Malaysia: Department of Environment 2010.

- Wood C (2003) Environmental Impact Assessment: A Comparative Review 2nd ed. Harlow, UK: Prentice Hall 2003.

- Andre P, Enserink B, Connor D, Croal P (2006) Public Participation International Best Practice Principles. Special Publication Series No. 4. USA: International Association for Impact Assessment 2006.

- Carpenter J, Brownill S (2008) Approaches to democratic involvement: widening community engagement in the English Planning System. Planning Theory & Practice 2008.

- Tewdwr-Jones M, Allmendinger P (2002) Conclusion: communicative planning, collaborative planning and the post-positivist planning theory landscape. In P Allmendinger & M Tewdwr-Jones (eds). Planning Futures: New Directions for Planning Theory. Oxon: Routledge 2002: 206-216.

- Lawrence DP (2003) Environmental Impact Assessment Practical Solutions to Recurrent Problems. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons 2003.

- Petts J (1999) Public participation and environmental impact assessment. In J Petts (ed). Handbook of Environmental Impact Assessment. V.1, Environmental Impact Assessment: Process, Methods and Potential Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science. 1999: 145-177.

- https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/foundations_course/IAP2_P2_Spectrum_FINAL.pdf

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-09/documents/spectrum508.pdf

- Marzuki A (2009) A review on public participation in environment impact assessment in Malaysia. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management. 2009.

- http://www.epa.wa.gov.au/step-step-through-proposal-assessment-process

- ELAW. New Zealand. 2017. Available: https://www.elaw.org/eialaw/new-zealand

- Ministry for the Environment. An everyday guide to the RMA – Applying for a resource consent. Wellington. New Zealand: Ministry for the Environment 2015.

- EPA. EPA assessment reports. 2017. Available: http://www.epa.wa.gov.au/epa-assessment-reports

- https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/12/26/myhsrs-eia-report-ready-for-public-viewing/

- https://www.epa.govt.nz/public-consultations/

- NREB (2019) The Natural Resources and Environment Ordinance (Prescribed Activities) Order 1994. 2019.