Abstract

Healthy Boundaries Relationship Model is a comprehensive discussion about the dynamics of maintaining respectful boundaries to protect your marriage. Emotional affairs and manipulating people who intrude on married couples or committed couples are problematic when proper boundaries are not maintained. Emotional affairs are not widely acknowledged compared to sexual affairs. Hidden in the guise of ‘friends only’ status can make them difficult to identify, yet, can easily ruin the best of any marriage or committed relationship. There are many influences and human flaws that can threaten your committed relationship through every day experiences. This article addresses couples with insight into the importance of exercising healthy boundaries to protect their relationship, along with identifying ploys from manipulative people, what an emotional affair looks like, and guidelines to help couples protect and/or restore their marriage.

Keywords

marriage, spouse, boundaries, manipulation, emotional affairs, third-party

Healthy Boundaries Relationship Model

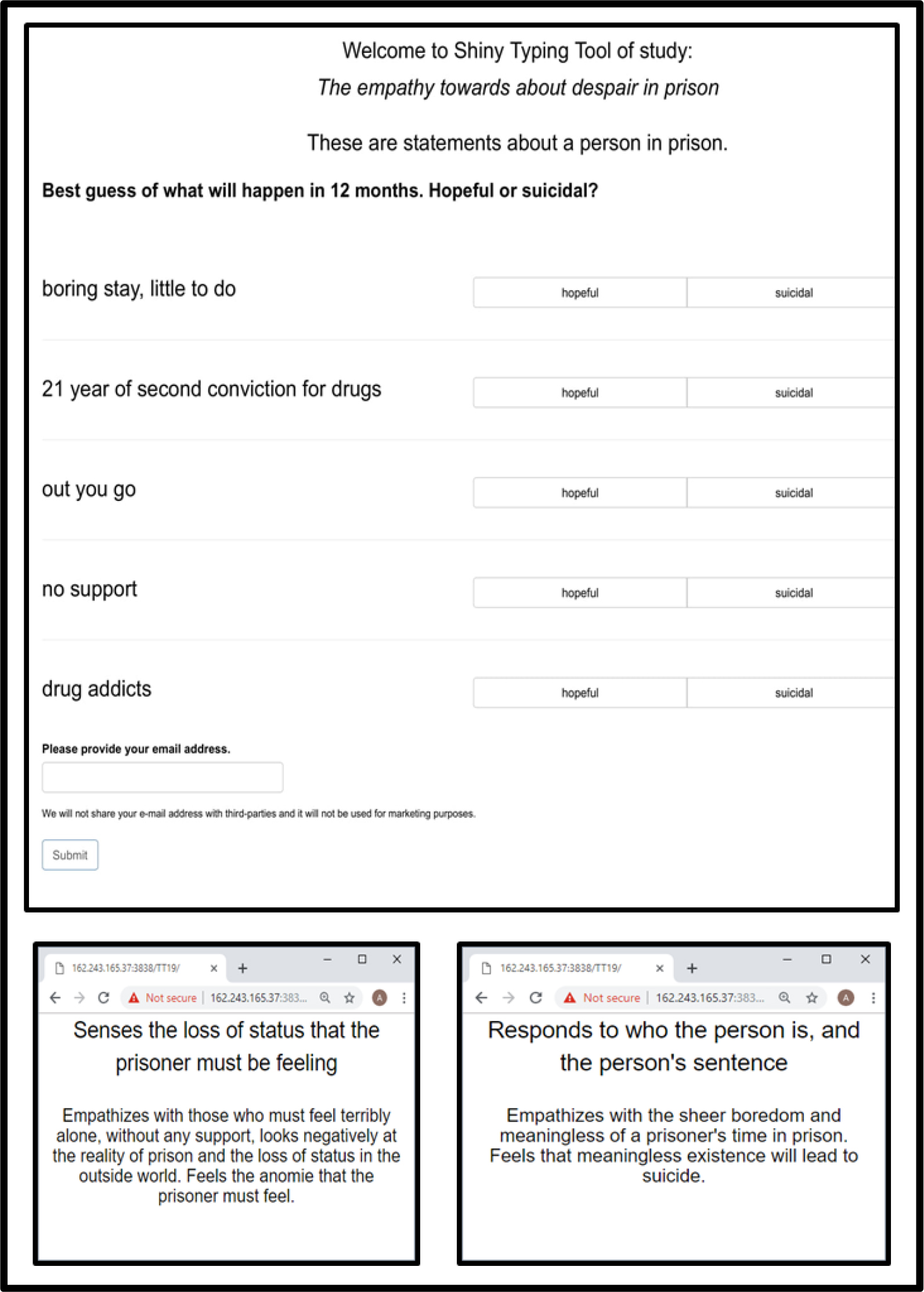

Healthy Boundaries Relationship Model is a relationship model that outlines boundaries for a married couple or any couple in a committed loving relationship. As there are no guidelines that rule every couple, there are, however, compelling reasons for every couple to decide where boundaries lie for them in reference to opposite sex-friends, or any person posing as a romantic threat [1]. This dialogue theorizes the topic of affairs and healthy boundaries while simultaneously addressing couples in a committed relationship. It will maintain the terms ‘third- party friendship, third-party relationship, third-party person or intruder,’ as any type of third- party relationship that is outside of, or separate, or secret from the committed relationship which poses a romantic threat. For the sake of simplifying vocabulary, the terms ‘marriage and spouse’ refers to any type of committed loving relationship between two adult people.

What is a Boundary?

Boundaries come in all shapes and sizes. Psychological boundaries are invisible mental guidelines that determine what we do and do not do, and, what we will and will not accept in our lives. They are created when we realize where our limits are. Boundaries reflect our values, thoughts, and feelings that are important to us, and are held together by our actions. We create boundaries to protect the things we love [2].

We love our home; we lock the doors for safety to protect our possessions inside. We love ourselves; we create boundaries to protect ourselves from harm and hurt from others. We love our families; we create boundaries to protect them and the relationships we share with them. We love our partner. We love the love we feel inside our hearts from them. We love our relationship with them, and the sacred space that fills the intimacy in our bond with them. We create boundaries for our marriage to protect our partner and our relationship. Boundaries regarding third-party friendships are guidelines that the couple decides upon to protect their marriage.

When we have healthy boundaries in our relationship, we take into consideration how our partner feels. We show appreciation and respect for the differences in our opinions, but most especially show respect for each other’s feelings. In relationships with unhealthy boundaries we may be unknowledgeable, or assume our partner feels the same way we do in any various situations where we may inadvertently overstep proper boundaries causing misunderstandings, and perhaps great pain [3]. The Healthy Boundaries Relationship Model holds each other’s feelings in check with a responsibility to support the integrity of the relationship, support trust, and respect for each other. Each person is accountable for their behavior. To live by, ‘putting your relationship first before your need to be right or in competition with outside demands and influences’ [4] places boundaries at the top of the list as one tool to ensure a healthy relationship with your loved one, your spouse.

Why Have Boundaries?

The simple truth about taking measures to protect your marriage is based on the fact that we are all sentient human beings; meaning, we have the capacity for awareness, feelings, responding, and reacting to others [5]. This is not to suggest you are a promiscuous person by nature ready to fall into bed with anyone who comes along, or that you are a deliberate betrayer. But you are a human being with the capacity to feel, interact, respond with feelings, and have relationships. Being a sentient being is the foundation of human nature, and no one is immune to it. Avoiding situations that may provoke feelings of attraction, emotional or any type of unhealthy involvement, neediness, or desires for someone else that may threaten your marriage is living within the guidelines of healthy boundaries for you and your spouse. We protect the things that we love. Our ability to protect our marriage is related to the strength of the boundaries we maintain, emotional or physical [6]. Our boundaries are maintained by our actions [2].

Defining Boundaries: The first step in setting boundaries is through self-knowledge.

Learn what is important to you [3]. Boundaries set the tone for how much we allow others to influence us emotionally. Based on the thought that most people make decisions because of their emotions instead of logic, healthy boundaries deflect outside influences that may put our marriage at risk from unhealthy influences or a misunderstanding with your spouse.

A misunderstanding, for example, if you are spending large amounts of time with a third- party person, or interacting in ways that seem overly friendly, perhaps appearing flirtatious, your spouse may become very hurt and upset. You may have not thought anything about it, assuming it was harmless fun. By maintaining awareness of boundaries to place your marriage first, these types of situations can be avoided or managed appropriately. In other words, boundaries place responsibility upon you to conduct yourself appropriately with others, and how you allow others to interact with you.

Thirdly, boundaries define who you are as a couple. It provides the foundation of trust that each of you will conduct yourself properly with the outside world when you are not together. It is an announcement to the outside world that you are a couple, not a single person available to the wind of other people’s desires, influences, and interests. Healthy boundaries puts your marriage first because it demonstrates respect for your spouse while reinforcing trust. It supports trust through the concept and exercise of healthy boundaries because healthy boundaries provide an umbrella of emotional safety. Do not underestimate the importance of boundaries in your marriage and in your life.

What are the Risks?

Statistics say that approximately 40% of all marriages will experience an affair [7]. There are many reasons why a person chooses to be unfaithful. The reason may be personal insecurities or character flaws which may not be reflective of the marriage at all, or of their partner [8]. Often, however, people fall into having an affair when they least expect from a seemingly harmless friendship. Feelings of neglect, conflict in your marriage, feeling an emotional void, frustrated, and angry may lead you to seek emotional comfort outside of the marriage. Stress and vulnerability may influence you to lower your guard without realizing it [7] or lose sight of your boundaries altogether. You are a sentient being. You have feelings and needs and wants just like anyone else. Naiveté and vulnerability can easily take control of you when you are not in control of yourself. Exercising healthy boundaries in your behavior is exercising self-control. No matter how stressful your marriage is, there is never a good reason for having an affair, as the aftermath is always heart-shattering. In every situation of unfaithfulness, however, having an affair is not a couple’s choice. It is always the choice of one member in the marriage who decided to step outside of the relationship [9].

Individual Boundaries

Some people may not be aware of the concept of boundaries. The risk of not having boundaries leaves a person wide open to following paths that they may have never intended to go. If you were raised in a home where boundaries were violated, never acknowledged or respected, you may not have an understanding of boundaries for yourself. Many people fear that enforcing boundaries, as in when you say ‘no’ is rude. Their need for approval takes priority over saying no. Thus, their fear of rejection outweighs their ability to set healthy boundaries [2].

Learning your own sense of boundaries as an individual ground’s you with personal strength to express who you are. Expressing your boundary is not an argument with anyone, it’s a statement about you, “This is who I am.” Personal boundaries are about respecting yourself, setting a stance for your individuality upholding standards that are right for you. It demonstrates you have control of your life [9]. It is not an argument. It is not a persuasive conversation with someone. It is an act of living your life authentically by upholding what you value. If you don’t uphold your boundaries for values that are important to you, more than likely no one else will either. Some people will try to manipulate you away from your values. But your boundaries will protect what you value, and prevent you from falling to the persuasion of others [2]. Healthy personal boundaries are just as important as relationship boundaries. Know your limits as an individual. Know what you will and will not tolerate, or participate in. Boundaries are guides for you to live authentically, and confidently with your true self. Although the concept of boundaries may seem rigid, it is not putting up walls around yourself from others. It is accepting and respecting yourself while respecting others. There is a gentle flexibility in exercising boundaries without building walls or losing the distinction of your individuality [6].

Third-Party Manipulators

While some people have no concept of boundaries, or simply do not have a defined set of boundaries, some people may know boundaries well enough to manipulate others. In fact, they may be inclined to manipulate your boundaries without your awareness. How so? In any multitude of ways: flattery, insincere emotional support, pretending to support your values when they themselves do not have values. They may share in a membership with you, clubs, or an organization. They may ask your advice when they already know the answer, asking favors of you [10] a friendly touch on the shoulder, and so forth are all examples of manipulative, coercing gestures.

There are many types of psychological manipulations that may seem like normal conversations and interactions. While it may seem normal and friendly, a third-party intruder may have maleficent intent to covertly intrude on your marriage with no concern about the effect it may have on you or your spouse. You are a sentient being. You have the capacity for feelings and responding like most normal people. A manipulative person knows this and uses it to their advantage. Understanding the manipulative mechanisms of third-party intruders is imperative for identifying them before you or your spouse are pulled in to the guise of their ploys. Knowing why people manipulate, and what manipulation looks like is valuable to prevent manipulation from occurring in the first place, can save from unpleasant situations, and perhaps lives.

For example, in 1978 the cult leader, Jim Jones psychologically manipulated over 900 people to commit suicide by drinking grape punch laced with cyanide. Before this suicidal measure of devotion, these vulnerable people were manipulated to turn on their families, and disconnected from them to follow his teachings and lifestyle. Once this was accomplished, he then manipulated his cult members into abusive acts, and to ultimately turn on each other if they did not follow the rules [11]. These people were extremely vulnerable and became victims of manipulation in the worst way.

Frailty of the Human Mind

There is a fundamental weakness in the human mind, a truth that applies to all. We are all at risk to the frailties of human nature, and subject to the persuasion of others [11]. Having vulnerabilities, and being vulnerable is part of the human experience. The Jim Jones story is an extreme example of manipulation. But manipulative tactics that influence us cannot be underscored in everyday life, including personal relationships. The psychodynamics of persuasion influences us in nearly every area of life every day [12]. Advertisement, music, art, literature, public speakers, corporate leaders for the organization we work for, conversations and interactions with friends, peers, family, and so forth all influence us throughout the day. A third-party person from our everyday life, who knows how to manipulate boundaries can influence any one of us without our awareness. We are sentient beings. We respond. We feel. We think the best of people by nature, without realizing others may not have the best of intentions for us.

What is Manipulation?

By definition, manipulation is the ability to influence another person by circumventing their sense of reason, with deliberate intent to induce a faulted thought or perception, a belief, a desire, or an emotion into someone [13]. The effect on the victim being manipulated results in a distortion in their normal decision-making process, which leads them to a thought, a feeling, a belief, a decision, or an action without knowledge of the manipulation being placed upon them. It is most generally viewed as an act that aims, “To achieve a desired goal using deception, coercion, and trickery, without regard for the interests or needs of those used in the process,” [14]. The style of manipulation can be covertly or aggressively. Covert measures are implemented in a manner that is secret, hidden, or not easily noticed. This form of manipulation is applied to win support from another individual, or group. This influence is focused on personal gain without concern of harm to others, achieved through acts of preying on another by using misleading messages, complaints, hidden intentions, and strategies. The personal gain for the third-party intruder is without empathy towards others affected by the manipulation [13] which means you or your spouse.

What is Their Motivation?

People with manipulative tendencies are often individuals with deep-rooted psychological insecurities. Their success in persuading others feeds their ego, leaving them with feelings of personal power. It is an ego-boosting method of building self-esteem that is, in reality, deeply missing. There are many types of personality disorders that classify maladaptive behaviors, manipulativeness, and apathy towards others.

To simplify, women, for example, who have affairs with married men, may find the experience thrilling from the perspective of the accomplishment to persuade him away from his marital commitment. A married man committed to his marriage, his love, his life with his spouse, his home and so forth has a lot to lose. The single woman who coerces him into a third- party relationship sees that through her persuasive efforts in her manipulation, he chose her, not his commitment to his marriage. Her accomplishment of luring him into the third-party relationship is an ego boost to nurture her low self-esteem. The accomplishment of winning his attention is the reward, as opposed to having a sincere healthy relationship.

Some people like toying with the energy of drama. One phone call or misplaced text message could destroy a marriage. Other women who desires a beautiful marriage sees love and happiness in the interactions of another couple. The single woman desires what that happy wife has, and pursues the husband. Fear of commitment, or simply looking for a father figure are other reasons for this type of behavior. Career women may not want the responsibility of a real relationship, but merely like the attention an affair offers [3]. There is a myriad of reasons why women do this.

Single men who have affairs with married women may lend itself to the fun of a carefree romantic relationship with no commitment on his part. A married woman with children, for example, is not available for a real relationship that involves dating, meeting each other’s friends and family. It creates a relationship for the single man, with no expectations and no responsibility. There is no need for dinner dates, remembering special anniversaries, or expenses. The focus is all about fun.

Underlying in both men and women from all walks of life, however, who intrude into committed relationships may represent a deep psychological aberrancy, as opposed to casual irresponsibility. The aim of a third-party intruder who violates the boundaries of a married couple through influence, persuasion, friendliness and so forth, is to win you or your partner’s attention. Their focus is to satisfy their personal needs and interests without consideration to either member of the marriage. There is no empathy on the part of the third-party intruder, they are manipulators.

Examples of Third-Party Manipulators

There are many examples of manipulation. Asking favors of you is an easy way to win someone’s attention. For example, the third-party person asks you to come to their house to help with a kitchen repair. Without telling your spouse you agree to help out. It seems easy enough, you’re in the neighborhood, it won’t take long, and the third-party person is just a friend or an acquaintance. While working on the repair the conversation becomes more friendly and casual. A separate personal friendship has been initiated. It seems harmless, after all, it was just a repair and conversation doesn’t hurt anything. Helping with a repair and talking is far from having an affair. It’s just being helpful to the third-party friend whom your spouse does not know you engaged upon. “No harm, no foul,” you say, you were just helping with their kitchen. This innocent thought is exactly what the third-party intruder was counting on.

Another example, the third-party person may initiate a boundary violation by confiding personal information with you while encouraging you to divulge personal information as well. What harm is that? You may think it’s of no harm. It’s just conversation and no one will hear about it anyway. The harm is, it is sharing personal information which should probably remain private anyway.

For example, during the event of that conversation, something personal comes to mind. You then view this dialogue as an opportunity to seek clarification of your thoughts, or validate your thoughts, or give you new thoughts, or help the third-party person with their thoughts. The intimacy of this situation creates a disclosure of privacy between you and the third-party. What’s wrong with this scenario is, it creates a ‘shared disclosure of privacy’ that is bonded between you two confiding private information with each other. Entrusting each other to keep that disclosure private is the bonding element between you and your new third-party friend.

Trust and bonding have now been developed with the third-party person without giving it a second thought. After all, you were only trying to help with their kitchen. Or you were just seeking answers to a thought that had been on your mind. The third-party person was friendly enough to help you and now you feel better. Feeling better gives light to the third-party intruder as a nice person whom you now feel very grateful to. Because they were so helpful to your private dilemma, you feel better. In fact, ‘you feel so much better and so grateful, you may be inclined to help them again’ is the third-party’s manipulation to further pursue boundaries with you, you may have never dreamed of.

Additionally, the third-party person with whom you helped repair their kitchen is now ever so grateful to you, ‘it would be wonderful to pay you back someday’ further sinks the hook of the third-party person’s manipulation to keep the rapport going and maintain a nice friendship with you. After all, you were so nice to help them with their kitchen. It all seems friendly and innocent is the guise of the third-party intruder manipulating every angle of the interactions. In all sincerity, you are a nice person, and now, without awareness, you are becoming a victim of their ploy.

Granted, there is nothing wrong with helping others. There is nothing wrong with appreciation when you are helped in return. When couples are specific about their boundaries for their relationship, such as no secrets, the expectations, the marriage, and third-party friendships can be very stable [3]. The scenarios above created a violation of healthy boundaries because your spouse did not know you went to the third-party person’s home, spending time alone with them to repair their kitchen. And because personal information was shared privately. Trust between you and your new third-party friend was held with an unspoken understanding that it would remain private, also created an unspoken bond between you two.

This third-party person with whom you feel good about, is in actuality, a manipulative third- party intruder, and you are not yet aware. The third-party relationship that was initiated outside the boundaries of your marriage has created triangulation. Three is always a crowd.

Another example, the third party-person may kick up a fun, flirty conversation with you at work, and asks to go to lunch with you. Perhaps they explain they have no one else to eat lunch with, and you feel sorry for them. Or they accidentally forgot their wallet and have no lunch money. Another example, the third-party person specifically volunteers to be on work projects, or committees with you to engage in that one on one connection they are seeking. The list can go on indefinitely of third-party intrusions that appear perfectly harmless.

The point is, if you do not have boundaries within your character, and/or the guidelines of your marriage you can easily fall prey to outside third-party influences before you know it [15] Why? Because you are a sentient human being interacting with another sentient human being. Feelings emerge, they are reciprocated politely or in true sincerity, and an experience ensues [5]. Covert manipulation by the third-party person may not be their deliberate intent, however, it cannot be ruled out. Having no boundaries is a perfect recipe for disaster in these precarious situations. By following healthy boundaries, and maintaining awareness, you avoid situations that may place you with possible temptation, and/or innocent, yet, painful misunderstandings with your spouse.

Emotional Affairs

In the discussion of having an affair, everyone has their definition of the term. Most people refer to the term’s affair, adultery, unfaithful, infidelity, cheating, and two-timing as sexual intimacy with another person outside of their marriage. But what about those personal outside third-party friendships that include emotional involvement without sex? It’s just a special friend with whom you confide in, share aspects of your personal life with, maybe regularly, maybe several times throughout the week, and you like their companionship. “No harm,” you say, “We’re not having sex. We’re just friends.”

When a third-party friendship is created that involves an overabundant level of interest, interacting, trust, a desiring, or a need for companionship with that third-party person that is ongoing, perhaps daily, and without any sexual intimacy. The question is, is this third-party relationship that could ‘potentially’ pose a threat to your marriage; is that a boundary violation? There is no sex. But does this third-party relationship fit in the category of unfaithful?

Yes! Because it is an emotionally based involvement with another person outside of your committed relationship, your marriage. Because the third-party person, your friend, with whom you like, trust, appreciate, and value as a friend could potentially become more than a friend, could also potentially place you at the pinnacle of sexual temptation, nevertheless. Following the path of heart, mind, thoughts, words, actions, feelings, accompanied by no sense of boundaries is the perfect formula for unfaithfulness. Faithfulness starts in your heart. Faithfulness in a marriage is, and was, initiated within the heart and mind of the beholders committed to the marriage. Betrayal may be viewed as, “Any act, or life choice that does not prioritize the commitment and put your partner before all others,” [16].

Emotional involvement with a third-party intruder separate’s marriage into an emotional triangle. It creates emotional betrayal that cuts into the heart of the marriage where love is sacred, and most importantly where your commitment was initially commenced [1]. Commitment starts in your heart. When you become emotionally involved with the third-party person, you have violated the very foundation of faithfulness where your bond with your spouse began. Additionally, when your emotions are pulled outside of your marriage towards the third- party friend, you have distanced yourself from your spouse emotionally, and from your marital commitment [1]. This gap violates the covenant of your union emotionally in your love for each other. Following the path that commitment starts with feelings in your heart, is then carried to your mind, your thoughts, words, and actions which then creates your beautiful relationship.

Unfaithfulness follows the same pattern. Most people do not awaken on any given morning and suddenly decides to have an affair with someone that afternoon. The development is a process that starts in the heart and mind way before he or she acts on it. Betrayal, stepping out of the marriage unfaithfully takes time and follows the same path of your original commitment to your spouse: heart, mind, thoughts, words, action. An affair has ensued.

Emotional involvement with a third-party person who poses a threat to your marriage is the foundation of betrayal initiating infidelity at the core of your commitment to your spouse. It is an affair. It is an emotional affair. It is a betrayal of trust, an insult to the integrity of love, marriage, and your commitment to your spouse. ‘Love, honor, cherish and forgo all others’ lays the ground rules for marriage in the commitment that is based on love for and with your partner. Nowhere does that include an additional partner on the side who also fills your heart with emotional joy, contentment, needs, reassurance, or satisfaction to fill your day. ‘I love you, Honey. But let me check in with my third-party friend to settle my day. I will then be happy to spend the rest of my evening with you,’ is relationship suicide.

By thinking of love as a verb, an action word that represents your feelings; your love is best shown to your spouse by your actions. Honoring your marriage with behaviors that protect your commitment, as in exercising healthy boundaries with third-party intruders is an act of love for your spouse and to your marriage. Emotional affairs are just as damaging as sexual affairs, and most often lead to sexual affairs anyway. Healthy boundaries avoid these sentient pitfalls of human nature, which lends the thought ‘it is best to avoid them altogether,’ instead of working through them later down the road. Not only does exercising healthy boundaries demonstrate love for your spouse and your relationship. It is also an act of respecting your own integrity. It conveys the message, ‘I am a faithful loyal person to my loved one. Do not approach me in any other manner, thank you. Now we can be friends,’ – meaning healthy friends with respectful boundaries that honor your marriage.

What Does an Emotional Affair Look Like?

Emotional affairs can be complicated because they are easy to deny when there is no sexual intimacy involved. They are easy to hide from your spouse, “We’re just friends.” Self- denial may be an easy trap to fall into; after all, there is no sex. He or she is just a friend. With all of this roundabout denial, how do you know if you or your partner is participating in an emotional affair?

Several aspects come into play that may require a discerning eye of observation, self- reflection, awareness of boundaries, and agreements made within your marriage about outside third-party friendships. Most third-party relationships begin with an innocent association with each other. Work, school, the gym, community volunteer groups, your child’s sporting events, walking the dog with a neighbor every day, or anything that entails a commonality for the interaction are perfect examples of situations where innocent friendships with a third-party intruder can develop. If your awareness of boundaries is lost, or you never had one in the first place, a personal relationship can easily evolve which may seem harmless [1]. It may remain harmless. But based on the fact that we are all sentient beings [5] leaves everyone at risk for feelings to evolve and grow [15]. Manipulative third-party intruders know this.

The damage occurs when you begin sharing personal information with the third-party person regarding your feelings, personal information about your life or your marriage that should remain private [1]. Sharing problems about your personal life, your family, or your marriage, for example, with the third-party intruder is an advertisement that you are open to receive consoling [17] and in need of a shoulder to lean on. In turn, listening to the third-party friend share their personal information with you seeking help from you, creates the role of the damsel in distress waiting to be rescued – BY YOU! It can be very tempting to help out, while it simultaneously pulls you into developing feelings for the third-party person. You feel sorry for them. You feel good about yourself to be helpful and to be needed. And, because you are not sexually intimate with the person, guilt and remorse for crossing any inappropriate lines are thrown out the window to denial.

Examples of the Emotional Affair:

There are many examples of third-party relationships that are inappropriate. Generally speaking, characteristics include an over-involvement, over and above normal communications, or unreasonable amounts of time with the third-party person that exceeds the call of duty of work, volunteering, school, or any situation may be leaning in the directions of an inappropriate third-party relationship. There is no professional, community, committee, or athletic necessity to discuss or engage in personal issues with the third-party person other than the task needed for the job, project, athletic team, or working out.

Do you find yourself, or do you see your spouse frequently communicating with the third-party person for extraneous reasons that have nothing to do with work or the committee? Consider the idea, then, that work, or the community committee project, or your child’s athletic team may now be an excuse to maintain that inappropriate third-party relationship.

Detailed Examples:

If the relationship with a third-party person is held separate from your spouse, including secrets, discrete and high frequency interacting and communicating with the third-party person, inappropriate text messages filled with flattery, personal pictures, romantic pictures, sentimental pictures, everyday pictures of your activities for the day, pictures of your family activities, sexual pictures, ongoing sharing of your personal life with the third- party person, sending pictures of the third-party person to the third-party person accompanied with comments such as, “Here’s your beautiful smile,” is flirtatious and inappropriate. Deleting or hiding text messages or emails, ongoing encouraging comments with personal moral boosting supportive type comments for the third-party friend, late-night communications such as, “Are you okay? Do you need anything tonight?” or “I’m thinking of you and you should be here with me,” are all inappropriate forms of communications with a third-party person. Verbal or physical gestures suggesting flirtatiousness are inappropriate. All of these forms of communication have nothing to do with work, volunteer projects, or your child’s athletic team. Neediness, missing the third-party person throughout the day and wanting to touch base to just say, “Hi,” is an inappropriate involvement with a third-party person. Going to their home alone and without your knowledge, followed with an excuse, “I was just trying to help with their kitchen, and Oh! – why her dad was there,” is inappropriate and may be grounds for question.

Going out of town alone with the third-party person without your knowledge or approval, followed with angry excuses of, “It was just business!” is inappropriate, hurtful and unacceptable. Communications with the third-party person that eliminates acknowledgment of your spouse, or eliminates acknowledgment of your love for your spouse, disregards or is demeaning of your spouse in any way shape or form is inappropriate. Defensive anger and excuses when confronted about the dynamics of your relationship with the third-party person, the inability to let go of the third-party person when your spouse asks you to, demonstrates emotional involvement with the third-party intruder and is inappropriate. This onslaught of examples provided here, and perhaps many more, most likely indicates an inappropriate third-party relationship. Namely, an emotional affair, if not a sexual one.

Because there is (presumingly) no sexual interaction, and there may be no sexual attraction, the underlying element of deep involvement with the third-party person, with whom your spouse cannot identify within him or herself their involvement. Their emotional involvement with the third-party person can compare to an addiction filled with denial of their behaviors that are unhealthy, destructive, co-dependent, destroys trust, and is damaging to their closest most valued relationship, your marriage. It is easy to see in others what people do not see in themselves [18]. Denial is a powerful front to hide behind yourself when, in fact, your spouse sees right through you.

Draw the Line: Third-party friendships that do not include you, or you are not including your spouse is clearly off-limits. Get-togethers, conversations, and interactions with the third- party person that are private, secret, or frequently one-on-one with the third-party person indicate that triangulation has been created in your marriage. You or your spouse may be aware of these interactions, but most likely you may not be aware of all of them. Partial disclosure of the third- party friendship is a half-truth, which means it is deceptive by the mere nature of hiding the other half. When the extent of the interaction and ongoing communication with the third-party intruder is well beyond the scope that a spouse would consider casual, or intermittent, and most definitely does not include them, the third-party relationship must change, have defining boundaries placed upon it, or removed altogether.

Why?

If your spouse is involved with someone that makes you uncomfortable for any reason and they are not sexually involved; they state to you there is no sexual attraction, why worry about it? The larger question is why do they have this third-party relationship? Why do they hang on to it when you have expressed your discomfort? Why would they need a third-party companion, a threat to your relationship when they have you?

Because they are emotionally invested! They did not utilize healthy boundaries in their behavior with their third-party relationship and now they are involved with the person emotionally. Their third-party friend has, most likely, become a very good friend, and perhaps now their best friend. They are attached to a need for the third-party person. They are having an emotional affair.

The term ‘emotional affair’ may come across as harsh when confronting your spouse who is in denial of their behavior, or never heard the term ‘emotional affair.’ To rephrase the situation as ‘you are overly involved’ might be easier to digest, but ultimately suggests the same thing. The damsel in distress and the knight in shining armor might best describe your complaint about your spouse’s involvement with the third-party relationship that is uncomfortable for you. Your spouse should be rescuing you, not someone else.

Any individual, your spouse or yourself, who is unable to say ‘no’ to others when no is appropriate is a person without personal boundaries and is a spouse who is not respecting healthy relationship boundaries either. Your spouse needs to say no to the damsel in distress because no is appropriate, and the damsel needs to move on. Not all emotional affairs turn into sexual affairs. But consider the thought that emotional involvement is the normal gateway for physical involvement and the rest is history.

Manipulative third-party people know this, and perhaps, has implemented tactics to encourage this with you, or your spouse. If you have lost sight of your marital boundaries and are involved in a third-party relationship, you are not only unfaithful to your spouse, you are most likely, also, a victim of manipulation from the third-party intruder who took advantage of a relationship with you that should have remained proper.

Painful Effects of an Emotional Affair

Considering that the third-party relationship has remained on the emotional level only, the difficulty dealing with these situations lies in the guise of ‘we’re just friends.’ It seems harmless to the spouse participating in the third-party relationship justified in the understanding there is no sexual relationship. The spouse participating in the third-party relationship may feel no sexual attraction either; nevertheless, engages in an overabundant level of interest, caring, concern for the third-party intruder, and need for their attention in return.

By nature, people are social beings with needs, interests, and activities which do not always involve the spouse. Additionally, it is fair to say that one person, your spouse, cannot fill your every need. Having outside friendships is normal, and healthy. When unhealthy circumstances evolve, however, demonstrating symptoms of an emotional affair, the spouse observing the situation is left with feelings of uncertainty, missing pieces, feeling excluded, and worried the marriage has changed. The third-party relationship, the emotional affair, is an emotional intrusion to the marriage. The heart is the foundation of love and commitment. It’s the starting point. It houses our emotions, our feelings of love and attraction, hate and disgust, and everything in between. In our committed relationship, our marriage, the heart is sacred space reserved for each other. A third- party intruder is overstepping territory that once was exclusive for you only or your spouse.

If a spouse is participating in an inappropriate third-party relationship, an emotional affair, that foundation of love, affection, and commitment in the marriage has been disrupted. That emotional space where trust, closeness, loving comfort that nurtures the marriage is no longer two people but is now shared with a third-party. Sections of that emotional sphere initially reserved for you, or your spouse is now sectioned off for someone else, and is left off-limits to the spouse left hurting [19]. Sharing that emotional space betrays the foundation of ‘love, honor, respect, and forgo all others.’ The spouse left hurting is left feeling betrayed, disrespected, threatened by the mere nature of a third-party’s presence in your heart. When the hurting spouse confronts the issue, the spouse participating in the emotional affair responds with defensiveness, ‘we’re just friends.’ Each spouse is left feeling insulted from each other [19].

The spouse left hurting did not receive reassurance that he or she was seeking. The spouse accused of the affair is taken aback by what may be deemed as a false accusation to their faithfulness, an insult to their integrity. It is pointing light on their character with question, are you faithful? Are you trustworthy? Are you honest? Are you a person of integrity? Are you lying? What do you two do together? What do you two talk about? Why am I not included? Why are you involved with this person? Are you in love with this person? Why is this friendship so important to you?’ And many more questions about their emotional world that has become closed off, now reserved for someone else. The spouse hurting is left feeling bewildered, confused, threatened, betrayed, and abandoned to defensiveness that warrants no room for comfort, cohesiveness, or emotional union in their love. Instead, the spouse left hurting is accused of being insecure, controlling, jealous, and insulting the integrity of the spouse who participates in the third-party relationship that he or she views as a harmless friend.

The discord creates a gap between the spouses, making the third-party friend appear more appealing as a friend, and now needed for emotional support. This gap in the marriage will fester if left unattended. The spouse hurting sulks in sadness, alone in their pain no longer comforted by their loved one has been hurt twice. Once with the uncertainty of the third-party’s place in your heart, and second by rejection from their loved one of their fears and worries. The spouse within the third-party relationship unable to see the inappropriateness of their involvement struggles with acknowledging the improper dynamics of their third-party relationship, the change in their marriage, their spouse, and defends their character which has now been shattered by the mere nature of question and/or accusations. Both members of the marriage end up hurt, not because hurt was intended. But because a third-party became an emotional interference in the union between two people.

A third-party person intruding into someone’s marriage is an emotional boundary violation. The emotional space in a loving marriage is between two people, not three. Not two and a half, indulging in brief contact with the third-party person for a quick emotional fix once in a while. A loving committed relationship between two people is two people only.

Why It is Unfair For All Three

The psychological imbalance in an emotional affair affects all three members, the spouse who is participating in the affair, the third-party person, and the spouse who is left hurting. Emotional affairs can evolve into a deep emotional bond with the third-party person that fills your thoughts with great appreciation for the friendship and sometimes love. Most often it includes sharing personal secrets, deep thoughts, innermost wishes, and concerns and worries. Sharing these issues with the third-party person creates a transference of intimacy that would normally be shared with your spouse. These friendships can develop innocently, or perhaps manipulatively from a deliberate intruder.

The Participating Spouse: When the hurting spouse is left out of fulfilling this intimate role within the marriage, the spouse participating in the emotional affair pulls the third-party person in to play the role of companion, confidant, and the emotionally supportive partner. The unfairness this plays on the spouse participating in this situation is, the effect causes a bifurcation of consciousness. Or, a splitting of your heart emotionally into two directions for two different people. Your spouse is the primary person you loved well enough to initially marry. Rather than dealing with improving your marriage, the arrangement of having a third-party relationship is much easier to have your cake and eat it too. In other words, two people can nourish your needs while you do very little to fulfill your own needs or the needs of your marriage. Unfortunately, however, this limits your capacity to experience deep love with your spouse. You are cheating yourself from a wholehearted loving experience by partially loving two different people.

Marriage takes a concerted effort to be a good marriage. By participating in two relationships that fill your emotional needs; you are, in reality, denying yourself the discipline and skills for maintaining a healthy relationship with one person. You are denying yourself development to be a quality partner for anyone; and, you are not working on improving your marriage. In effect, you are passively having your needs met by two different people. This lack of personal development of not dealing with the demands of a quality marriage in a healthy manner may be the result of sincere clinical denial, unable to see the dysfunction of the relationship triangle. Or, it may be plain old apathy, meaning emotional indolence.

The Third-Party: Provided that the emotional affair evolved out of innocent friendliness, the unfairness of the emotional affair for the third-party person is, they are essentially being used to fulfill your emotional emptiness. Provided that the third-party person is not having a sexual relationship with you, they may fanaticize of having an intimate relationship, perhaps a serious relationship with you when you have no intentions or desires of going down that road. This holds the third-party person stationary in their life from perusing a healthy relationship with someone else who could love them wholeheartedly, instead of part-time when you feel the need for them. Essentially, you are cheating the third-party person from a having real relationship.

On the other hand, a third-party intruder who deliberately initiated the emotional affair manipulatively may be left with boredom and frustration when the thrill of accomplishment wears off and they did not find the fulfillment they had initially fantasized about.

The Hurting Spouse: The spouse left hurting is left hurting for obvious reasons. Betrayal of trust, secrecy, dishonesty, feeling threatened of losing your love, and emotional betrayal that their spouse, you, could have feelings or love for someone else. When the participating spouse does not engage their (hurting) spouse as their emotionally intimate partner, the spouse left hurting is, unknowingly, disadvantaged to nurture the marriage or their spouse appropriately.

The hurting spouse is cheated from knowing their partner wholeheartedly because the spouse participating in the emotional affair is diverting his or her thoughts and feelings somewhere else, to a third-party person. This adds to the emotional gap between the spouses because the hurting spouse is without awareness of the true person they are married to, thus, is unable to interact with their loved one to fulfill their needs. The spouse left hurting, unfortunately, is interacting with a façade the participating spouse presents to them, because the participating spouse is hiding their true self, in addition to hiding their involvement with their third-party friend. The hurting spouse is also cheated from receiving wholehearted love from their loved one because their loved one is pouring energy into someone else, the third-party person.

The emotional pain from these experiences can be long-lasting and take time to work through. Re-establishing trust can be a slow process with experiences of ups and downs before reaching comfort with each other. Placing your spouse through the pain and challenges of an emotional affair by not exercising healthy boundaries in your behavior is an unfair lack of consideration that could have been avoided altogether. The situation neglects personal growth and development within the marriage. The overall effect of an emotional affair is that all three parties end up with an incomplete relationship.

Never too Late to Learn

Healthy boundaries protect yourself, and your marriage from unwanted influences, or painful misunderstandings, which may be sincere misunderstandings. Healthy relationships have healthy boundaries that prevent third-party intruders from overstepping boundaries that should be reserved for your marriage. Marriage is a responsibility. When we are in a loving committed relationship, we have a responsibility to hold that love in our hands with honor, respect, and appreciation. This is carried out by exercising respectful boundaries in your behavior to protect your marriage. Allowing someone to step into your emotional space is disrespectful, and deeply hurtful.

If you have never thought of healthy boundaries it is never too late to learn. Make yourself, and your marriage a work in progress for life. The willingness to grow, to make changes with yourself and your marriage not only helps you get the love you want but helps you keep the love you want [20].

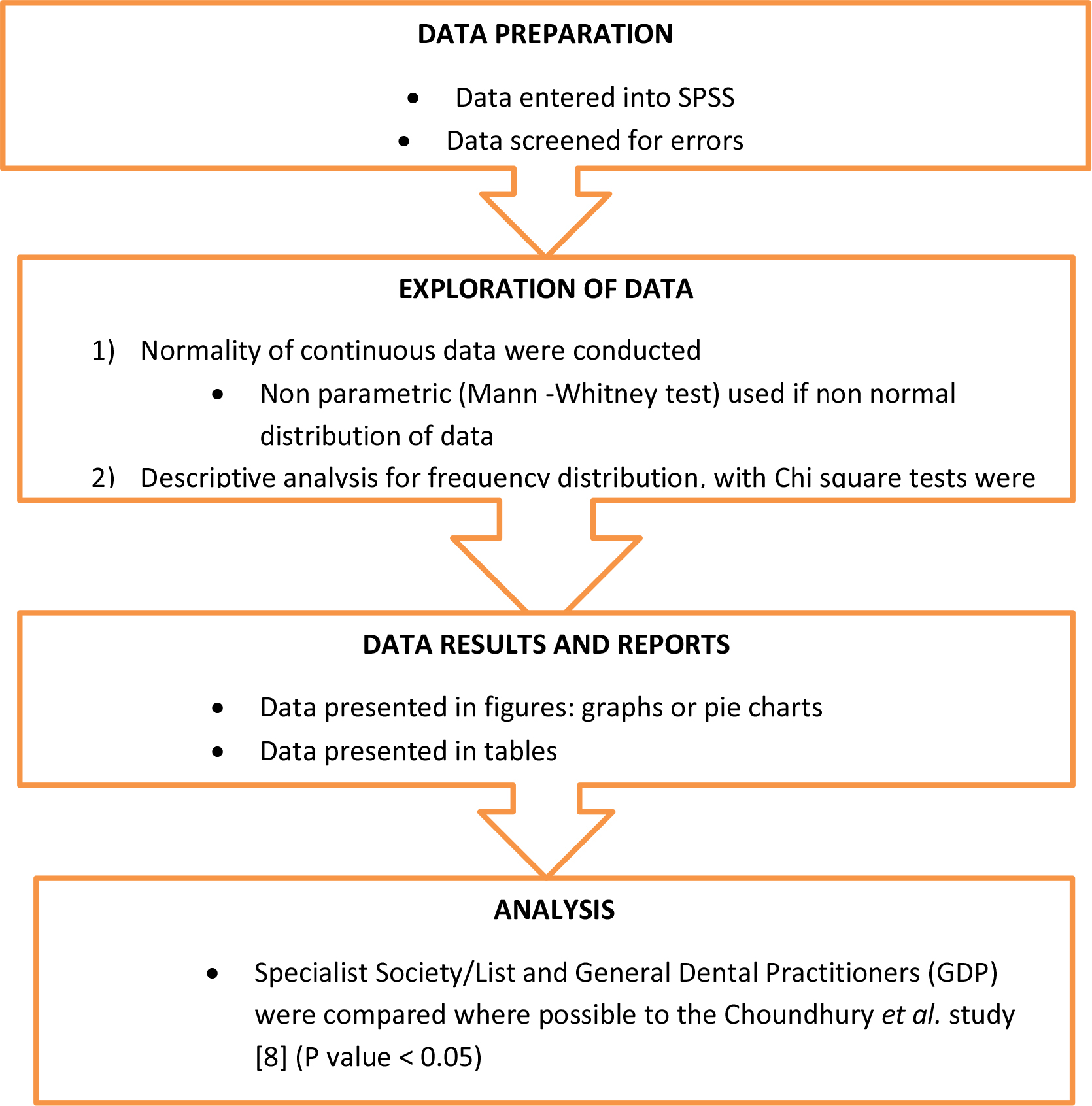

Guidelines for the Healthy Boundaries Relationship Model

To set the ground rules for the Healthy Boundaries Relationship Model, the list of do’s and don’ts apply to the understanding of ourselves as sentient human beings. No one gets married with the commitment of ‘I will betray you.’ The commitment is to love, honor, cherish, and forgo all others. While there is nothing wrong with healthy third-party relationships, honoring your marriage should always come first. It starts by exercising respectful boundaries in your behavior.

The Model

First and foremost, start with having a conversation with your loved one about your relationship. Nothing underscores the importance of communication. Decide where you draw the line with third-party friends [7]. When developing your relationship consider creating a relationship notebook, so you can jot down your agreements. This is not a legal binding contract. It is a friendly note pad of your thoughts, feelings, and decisions you make together to keep you on track of ‘the marriage comes first policy,’ and to not forget what you talked about.

Cultivate friends that each of you enjoys socializing with together. Invite the third-party friend, and their partner to become friends with your spouse [21]. If your third-party friend is single, your friendship with that third-party person should change when you enter your committed relationship, your marriage. You are no longer a single person readily available for personal activities that may have once been a part of your casual friendship.

Your third-party friend should understand this without explanation. However, some people need direction.

If there is a third-party relationship that already makes you, or your spouse uncomfortable, nip it in the bud immediately. Do not deliver, or accept any excuses to rationalize or defend the third-party relationship [21]. Your marriage comes first over and above anyone else. Set defining guidelines on how to manage the third-party relationship. It may involve simply ignoring the third-party person. It may require a conversation, a letter, a meeting between the three of you to set healthy boundaries or eliminate the third-party relationship altogether. Whatever is initiated to change the dynamics of the third- party relationship, has to be carried out, and most definitely, maintained.

If your spouse is uncomfortable with your third-party relationship and setting boundaries is not an option, complete disengagement from the third-party relationship may be the only option. There is no one more valuable in your life than your loved one, your spouse. A friend, the third-party friend who is truly a friend ‘only’ should respect that, knowing that their friendship with you is just a friendship. Not a personal selfish need of theirs to have you, or your spouse at their disposal for their personal interests. If the third-party person knows that you or your spouse is uncomfortable, they should be respectful; back off, apologize, make corrections, or stay away altogether. The third-party friend should respect both of you as a couple because you are a couple, not a single.

The spouse in question also has a responsibility to reassure their partner that boundaries with the third-party person are being maintained. This may require personal conversations, or an open pass to see text messages, cell phone call logs, or emails. Everyone has their limit of sharing, and most especially passwords. So, consider this a boundary issue in your marriage as well. Instead of free reign to see texts and emails, perhaps the openness of the spouse to randomly show you when you ask may be a polite option to open that boundary between you two. Transparency is a fabulous passage for building and maintaining trust.

Do not cultivate private relationships with third-party people who may pose a threat to your marriage in anyway shape or form. Instead, cultivate relationships with other couples, or friendships that offer no means of threat of any type. Heterosexual married people can cultivate close friendships with others of the same sex; who can, and may become your best friend outside your marriage [21]. This rule holds true for any type of committed relationship between two people who love each other. Define this for yourselves in your lifestyle and your marriage.

With co-workers, civic committee members, volunteer members, other parents of your child’s class or group, your child’s teacher, your neighbor, or anyone who has the potential to cause havoc in your marriage or risk the potential of overstepping healthy boundaries, should be addressed in the confines of their appropriate role. If it’s a co-worker stick to business [22]. If it’s a committee member, stick to the committee agenda and so forth. Avoid developing personal or private relationships, but create open relationships that include your spouse and the third-party’s loved one as well.

Specifics: Specific guidelines are for you and your spouse to consider: Do not go out to lunch, dinners, or happy hour drinks alone with a third-party person co-worker. Go as a group [1]. Do not meet alone with third-party people if possible. Have your office door open, or an office with blinds open if possible [7]. Do not go out of town with a third-party person alone [1] and probably not as a group either. Let that person make their own way to their destination. Consider taking your spouse with you when you go out of town for business or community projects that require travel. When you do travel out of town alone, make a point of calling your spouse every evening to check-in, or perhaps video chat. Offer reassurance of your love for them, and that you miss them. Rather there is an issue about boundaries or not, a little reassurance goes a long way to keep your marriage strong.

Be cognizant of a third-party intruder who demonstrates overly friendly gestures or flirting. Don’t feed into it. Ignore it, or tell the person you are uncomfortable. Do not deliver overly flattering comments that may come across as affectionate or flirtatious. Appropriate compliments have their natural place in all appropriate settings, so leave them there. Do not participate in conversations where you or the third-party opens the door for personal information. The privacy of your marriage is sacred space. Respect it and keep it private. Your problems with your spouse belong to you and your spouse, they are none of the third-party person’s business. Speak politely and kindly of the person you love to show the third- party person you are devoted to your spouse. Do not allow anyone to speak badly of your spouse with negative comments or name-calling. Always defend your spouse and inform the third-party person that insults and name-calling of any type are not acceptable in this manner. For the damsel in distress who needs your ear, encourage them to talk to the person they have the issue with, or get professional help [7]. You are not their therapist, and they are not yours either.

Do not keep secrets from your spouse at any time about your relationship, your feelings, or your interactions with a third-party friend. If you see that you are developing feelings for someone outside of your marriage talk to your spouse, or a therapist, but not the third-party person. Do not participate in personal private communications with the third-party person. This includes text messages, emails, private messages, any social media, Drop Box, video chats, or passing notes to each other at the office unless you are completely at ease to share it with your spouse. If your spouse becomes uncomfortable for reasons you did not anticipate, stop the communications. Take action to inform the third-party person that the private messages have to stop. Be honest with yourself about this and take care of it. If necessary, show your spouse that you took care of it and that there are no more communications. If communications cannot be discontinued for some reason, such as ex-spouses where children are involved, or other situations, see if copies of future correspondences can be openly shared with your spouse like a group text, or group email exchanges.

When out together and the third-party person is present with others, and/or a group event, avoid private dialogue with them that excludes your spouse. Include your spouse on the topic of the conversation that he or she may not understand if it is work-related for example. Or, avoid the third-party person altogether so you and your spouse can have a good time.

Reflect: Reflect inwardly. Are you feeling attracted to a third-party person? Do you think about them often, or compare them to your spouse? Would you be comfortable with your spouse doing any of the things you are doing with your third-party friend, that your spouse does not know about? Are you upholding your spouse’s requests? Or does the influence of your third- party relationship sway you from doing so? Do you and your third-party friend talk about your feelings for each other? Do you share your feelings and thoughts with your third-party friend more than your spouse? Do you isolate your third-party friendship away from your spouse? Do you feel sorry for the third party-person in such a way of taking on co-dependent behaviors to rescue them, to fix them, or fix their problems? Are you delivering excuses, defending your rationale for maintaining your third-party relationship when your spouse is uncomfortable, or highly upset about it? Is your third-party relationship coming between you and your spouse? Are you arguing about it? Has your committed relationship, your marriage broken up because of your involvement with a third-party friend?

If you answered yes to any of the above questions, you are in an inappropriate relationship with a third-party person. You are having an emotional affair, if not a sexual one. You are responsible for how you interact with others and how you allow them to interact with you. Be accountable for yourself as you would expect your spouse to do the same, and end the third-party relationship immediately. If your spouse is uncomfortable, do not dismiss their concerns. A wise person listens and respects the feelings of their loved one. Your marriage comes first, not the damsel in distress who can’t take care of him or herself emotionally, physically, financially, or in any manner. The same holds true if you are the one that is uncomfortable observing your spouse having a third- party friendship. Trust your intuitions! Confront your thoughts and your spouse honestly. Sooner is probably better than later.

Honesty: If you are in an affair of any type be honest with yourself. Be honest with your spouse. Honesty takes courage. As hard as it may be to face the embarrassment of confession and the fear of their reaction, it is much better to share the truth with your spouse than for them to find out otherwise. In many cases, the development of an outside friendship is not the insult to your spouse. It is the secrecy, the half-truths, and deception that betrays trust in your marital relationship that is most hurtful because it is a disregard for your spouse. And most especially, it ruins your character. It ruins the ‘good’ you with whom they knew and loved, which has now been lost to the pain of betrayal and the melting of trust that once embraced you both so lovingly.

Integrity starts with yourself. It belongs to you, so manage it in the best way possible. If you are afraid to be honest with your spouse about your feelings for your third-party friend, your emotional involvement, or sexual involvement, take comfort in the thought that your honesty may be a pivotal point in changing your marriage for the better. Your spouse will most likely be unhappy with the news, but they may ultimately respect you for finding the courage to be honest [23]. Honesty upholds the status of your integrity. Own it! Be honest with yourself and your spouse, because honesty may be your only option for staying in your marriage to make it work. Regardless of your spouse’s response, it goes without saying, change will occur.

You have been Confronted? If you have been confronted by your spouse about a third- party relationship that makes your spouse uncomfortable, fix it! Basic human nature needs to be social and have friends is not the insult. It’s the denial of your overabundant involvement. It’s the inability or refusal to make corrections with yourself to honor your spouse’s feelings that is insulting. To not make corrections with yourself and your third-party friendship is an insult not only to your spouse, but is insulting to your marriage, and yourself as well. Your marriage and your love for your spouse comes first over and above your excuses to rationalize your third-party friendship while denying your spouse’s requests and feelings. Take time to nurture your marriage. Address your concerns with your spouse constructively. Be respectful. Be trustworthy. Show trust with your actions that demonstrate faithfulness, protection of your marriage, and your love for each other. Address issues in your marriage that caused you to seek emotional solace outside of the marriage. Quality communication, sharing your thoughts and feelings, and personal interests may have been missing, and this is an opportunity to restore these things to your marriage. Your marriage comes first over and above anyone, and most especially to a third-party intruder.

Recommendations

There is much to learn about the frequency of emotional affairs and the dynamics that lead up to it. It is recommended that more research continue in the social-psychological sciences, and amongst marriage counselors to determine a set classification of symptoms and patterns of this heart-shattering relationship dynamic. The focus is to better help the spouse in distress who does not understand the behaviors, feelings, and the psycho-dynamics of their loved one who appears to be involved with a third-party person emotionally, yet, not sexually. For the spouse in question involved in a third-party relationship, who, perhaps, might be in denial; research and open discussions are avenues to guide that spouse to awareness of their actions and further self- reflection. More awareness of this topic through public forums, social media, and discussion panels will help educate the public to understand emotional affairs, third-party relationships, and preventative measures before they occur.

Conclusion

There are many philosophies, theories, and relationship models that emphasize techniques for putting your marriage first. Healthy Boundaries Relationship Model is only one perspective to do so. How you gauge your boundaries is a private decision between you and your spouse. This model merely provides guidance to help you define who you are, who you are as a couple, how to avoid manipulation, and how you hold your marriage together with happiness. In any situation, however, be your best. Be wise, discerning, and put your marriage first.

Insert

|

Do’s |

Don’ts |

|

|

References

- Cherry D (n.d.). Emotional affairs. Series about: Affairs and Adultery. Focus On The Family.

- Admin A (2014) Boundaries loving again after a pathological relationship. USA.

- Tartakovsky M (2018) Why healthy relationships always have boundaries & how to set boundaries in yours. Psych Central.

- Tatkin S (2011) Wired for love. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. USA Today. (1996, August). Many single women prefer married men. USA Today, 125.

- Ramsay K Life coaching certificate course (beginner to advanced). Udemy.

- Katherine A (1991). Boundaries where you end and where I begin. Center City, MN: Hazeldon.

- Caston M (2017) How to keep boundaries with the opposite sex.

- Cloud H, Townsend J (2000) Boundaries in dating. Orange, CA: Yates & Yates.

- Cloud H, Townsend J (1999) Boundaries in marriage. Orange, CA: Yates & Yates.

- Grant A (2014) Seven sneaky tactics that sway. Psychology Today 47: 43–44.

- Harrary K (1992) The truth about Jones town. Psychology Today 25: 62.

- Sarkissian H (2017) Situationism, manipulation, objective self-awareness. Ethical theory & Moral Practice. 20: 489–503.

- Noggle R (2017) Manipulations, salience, and nudges. Wiley Bioethics.

- Potter N (2006) What is manipulative behavior, anyway? Journal of Personality Disorders 20: 139–156.

- Daly J (2014) Keeping healthy boundaries. The Winnipeg Sun.

- Gottman J, Silver N (1999) Chapter 2 What does make marriage work. The seven principles for making marriage work (2ndedn). (p. 26). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Mental Health (n.d.) Just answer mental health.

- Parr A (n.d.) Opposite sex friendships? Allen Parr Ministries.

- Lustbader W (2014) Emotional affairs: Why they hurt so much. Psychology Today.

- Hendrix H, Hunt H (1998) Getting the love you want. A guide for couples. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

- Focus On The Family (n.d.). The Billy Graham rule: Should you be friends with someone of the opposite sex? Focus On The Family.

- Eckel S (2019) The power of boundaries. Psychology Today.

- Christy H (2017) The importance of being honest in marriage.