Abstract

Objective: To explore the role of parental education and communication of risks versus benefits of pediatric dental image on parents’ knowledge, comfort and confidence in allowing their children to receive the necessary imaging procedures.

Methods: Parents of children <18 years of age were recruited during routine dental visits at the Boston University Pediatric Oral Health Care Center and Department of Dentistry at the Boston Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. Participants completed two brief questionnaires immediately before and after the educational intervention. A brief two-sided printed informational handout and a mobile application called Medical Imaging Risk (MIR) were used in the educational intervention for parental health education and communication of information on radiation risks. Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA version 14.0 to compare pre-intervention and post-intervention responses of participants.

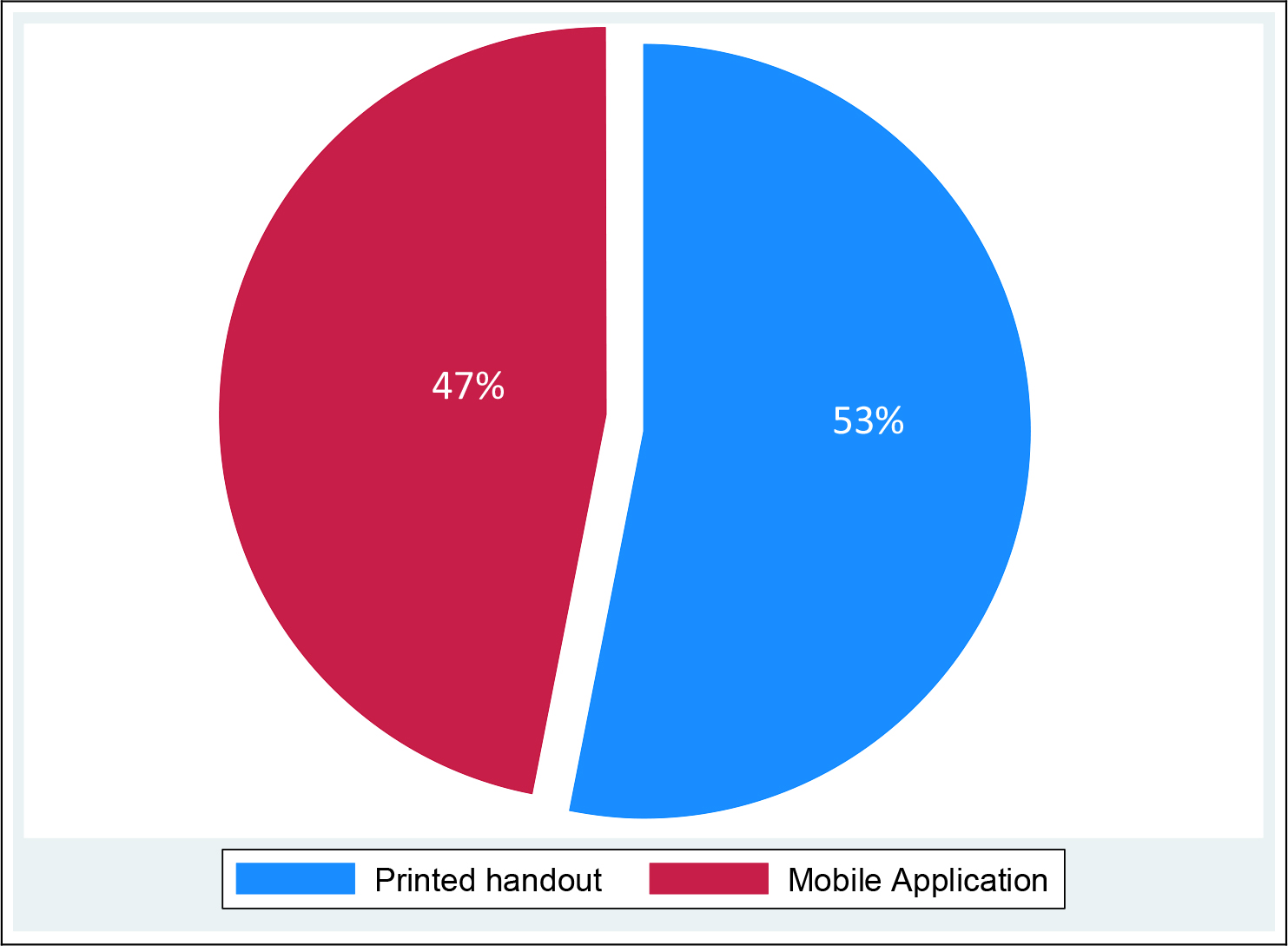

Results: Among 213 parents, the majorities were mothers (83%), African American (55%), with MassHealth insurance (82%) and reported that their child/children have had previous dental radiographs (75%). A significant improvement in confidence of their knowledge on benefits and risks of dental imaging was observed following the educational intervention (p<0.001). Parents’ level of comfort in allowing the use of dental radiographs for their children significantly improved after the educational intervention (p<0.001). Parents preferred the printed handout (53%) only slightly more than the mobile application (47%).

Conclusion: The results from our study suggest that a simple brief educational intervention that includes easy to understand materials can significantly improve parental level of knowledge and confidence towards pediatric dental imaging. Thus dental practitioners should aim to include risk-benefit dialogues as part of the routine dental care visit to improve communication and acceptance of pediatric imaging.

Keywords

Health Communication, Pediatric Dentistry, Children, Radiation Imaging, Radiation Risks, Dental Imaging, Dental Radiography, Parental Knowledge, Educational Intervention.

Introduction

Patient communication of health information is a key component of patient care and management. In particular, communicating risks and benefits of medical and dental procedures enables better understanding and decreases the level of anxiety among patients. Radiation imaging has been known to cause fear and anxiety among patients due to the general perception of radiation as a ‘hazard’ [1]. This fear, caused mainly by incomplete understanding of the benefits versus risks of radiation imaging, has been further fueled by historical radiation related disasters, media reports, social media, previous experience, experiences or shared by family and friends. Recent evidence in the literature also suggests that significant gaps exist between patient expectations and provider communication of benefits versus risks of medical imaging [2]. These gaps also extend to dental imaging procedures which can be overcome through improved risk-benefit dialogues between practitioners and children, and their parents or guardians. To improve the current practices in risk communication strategies the World Health Organization (WHO) organized an International Workshop on Radiation Risk Communication in Pediatric Imaging in September of 2010 and in collaboration with a working group released a publication titled “Communicating Radiation Risks in Paediatric Imaging” [3]. This publication was developed to aid health professionals on communication of radiation risks in pediatric imaging more efficiently and to provide guidance on risk-benefit dialogues with children and their parents.

Dental radiology has evolved over the years and is currently being used widely in children for diagnosis and management. In pediatric dentistry in particular, dental imaging has played an important role in a child’s first visit to the dentist as it is not only a vital part in a thorough examination of the oral cavity but is a simple procedure that is used to also gain the child’s confidence [4]. While radiation emission from dental imaging is lower than from medical imaging procedures, dental practitioners should weigh the benefit and need for the imaging procedure among children over the risks involved to make a clinical judgement keeping in mind the interest of each patient. In recent years there has been a significant increase in the use of dental radiography in the United States (US) with over 500 million intra-oral bitewing and panoramic radiographic procedures [5]. Also, the number of Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) procedures have also significantly increased over the years. As a result, the overall contribution of radiation exposure from dental imaging procedures is increasing and is about 50% of the annual per capital radiation dose in the US [6]. In light of these increases the American Dental Association (ADA) in collaboration with 80 other health care organizations developed a program called ‘Image Gently’ in 2007 which is an initiative to raise awareness and educate practitioners to provide safe pediatric imaging [7]. This alliance was also developed to educate providers on selecting imaging procedures based on individual needs and to limit the exposure time among children. The ‘Image Gently in Dentistry’ campaign was specifically launched to promote responsible use of dental radiography and to improve radiation safety in pediatric dental imaging [6]. The main goals of this campaign is based on the concept of reducing radiation exposure in children As Low As Diagnostically Acceptable (ALADA) while achieving effective images that aid in diagnosis.

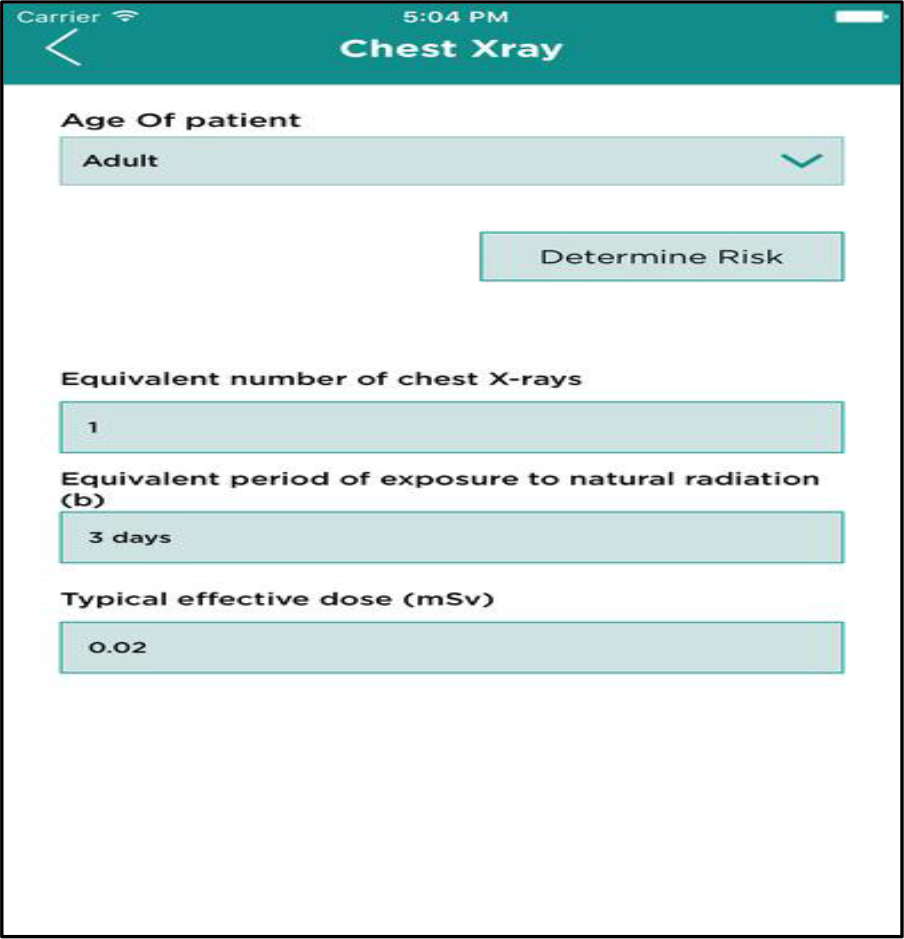

Radiation exposure is the amount of radiation charge produced by ionizing radiation during imaging procedures whereas absorbed dose describes the amount of emitted radiation absorbed at a point [8]. This absorbed dose is converted to equivalent dose by multiplying the radiation delivered for each type of radiation. Effective dose is the total amount of radiation exposure estimated from the total equivalent dosages and [3] can be expressed in Sieverts (Sv) based on the System International nomenclature [3]. The radiation dose emitted in diagnostic imaging is expressed as milliSieverts (mSv) [9]. When comparing the radiation exposure between medical imaging procedures versus dental imaging, the exposure from dental radiographs are much lower. For example, the radiation dose from a set of four intra-oral bite-wing radiographs is 0.005 mSv and from a single panoramic radiograph is 0.01 mSv which is equivalent to <1 day and 1.5 days of exposure to natural radiation respectively [3,8]. In comparison, the radiation exposure from a chest x-ray for a 5 year old child is 0.02 mSv which is equivalent to 3 days of natural radiation exposure. A Computed Tomography (CT) scan to the head of a 5 year old emits 2 mSv radiation and is equivalent to 10 months of natural radiation exposure whereas one CBCT procedure leads to radiation exposure of 0.107 mSv which is less than five months of natural radiation exposure, demonstrating that dental imaging procedures lead to much lower radiation exposure. The risks from exposure resulting from all types of diagnostic imaging and its effects are not completely understood [3]. Effects such as cell death, hair loss, skin redness etc. occur at much higher doses of exposure than the exposure from dental diagnostic imaging. Long-term risk of developing cancer has been suggested based on some epidemiologic evidence for radiation doses of 50–100 mSv which would be the accumulated dose after multiple CT scans. However, since children have a long period of life ahead, the low dose exposures from diagnostic imaging in the early years of life may accrue and eventually may lead to a small increase in lifetime risk of cancer in the future. Hence given the lack of strong evidence and the uncertainty it is important for dental practitioners to take a precautionary approach when using pediatric imaging. Also, by improving patient and parent-provider communication about risks versus benefits, informed decisions can be made that will ultimately benefit the child patients.

There are only a few studies that explored the perspectives of parents and communication of radiation risks most of which are related to medical imaging procedures. Limited evidence exists on communication of dental radiation risks and parents’ knowledge and perception towards dental radiography. A study in Australia explored parental level of knowledge and attitude towards dental radiography for children [10]. That study analyzed 309 surveys completed by parents and the results showed a low level of knowledge but positive attitude towards dental radiographs. Also in that study, parents’ level of education and parents with children who have had radiographs previously were more likely to have a higher level of knowledge. In the same study when participants were asked about whether they received information on radiation risks, <40% reported that they had been informed of the risks by their providers. Similar findings have been reported in studies on medical imaging where participants have low level of knowledge and report that they did not receive the information on the risks of medical imaging [11,12]. A more recent study evaluated patients’ perception on dental radiographs in Malaysia and reported a significant lack of knowledge about the role of dental radiographs. In that study among the participants 57% believed that dental radiographs should be avoided in pregnant women and 32% believed that dental radiographs should be avoided in children [13]. Studies on communicating risks clearly highlight the gaps in provider-patient or parent communication. Evidence also suggests that parents who did receive information prior to imaging procedures report lower levels of anxiety during the procedures [11]. Insufficient data is available on the preferred method of communication in dental imaging risks versus benefits. One study in Spain among 602 participants reported that participants preferred both oral and written forms of communication with no significant preference of one over the other [14]. With the current technological advances there is an increase in usage of other modes of communication such as online resources, phone applications and text messaging however there is a lack of epidemiological data that supports the use of these methods and there is insufficient evidence on the most effective form of communication of health information.

Our study was developed to explore the role of parental education and communication of risks versus benefits of dental imaging on parents’ knowledge, comfort and confidence in allowing their children to receive the necessary dental imaging. Results from our pilot study has been published previously [15,16]. In this report we describe the study that was conducted and the results obtained from a larger sample with additional investigation on the preferred method of communication of risks versus benefits in comparison to our pilot study. Specifically our hypothesis was that a brief educational intervention by the dental provider will increase the level of confidence and comfort among parents and those parents prefer a specific mode of communication of health information.

Methods

Note: A description of the study methods and results from our pilot study was published previously [15,16].

The sample population in this study included parents or guardians of children under 18 years of age. The participants were recruited during routine dental care visits for their children at either the Pediatric Oral Health Care Center in Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine or Department of Pediatric Dentistry at the Boston Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. A convenience sampling method was used to recruit any one parent or legal guardian per family and only those who were proficient in the English language were included. Following verbal consent, the parents completed two brief questionnaires and an intervention using a handout and a mobile phone application was conducted as well by the study investigator. The parents completed the questionnaires and the intervention while waiting during their children’s dental treatment. The time taken for participants to complete the questionnaires and the educational intervention was between 15–20 minutes. This study was approved by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Educational Intervention

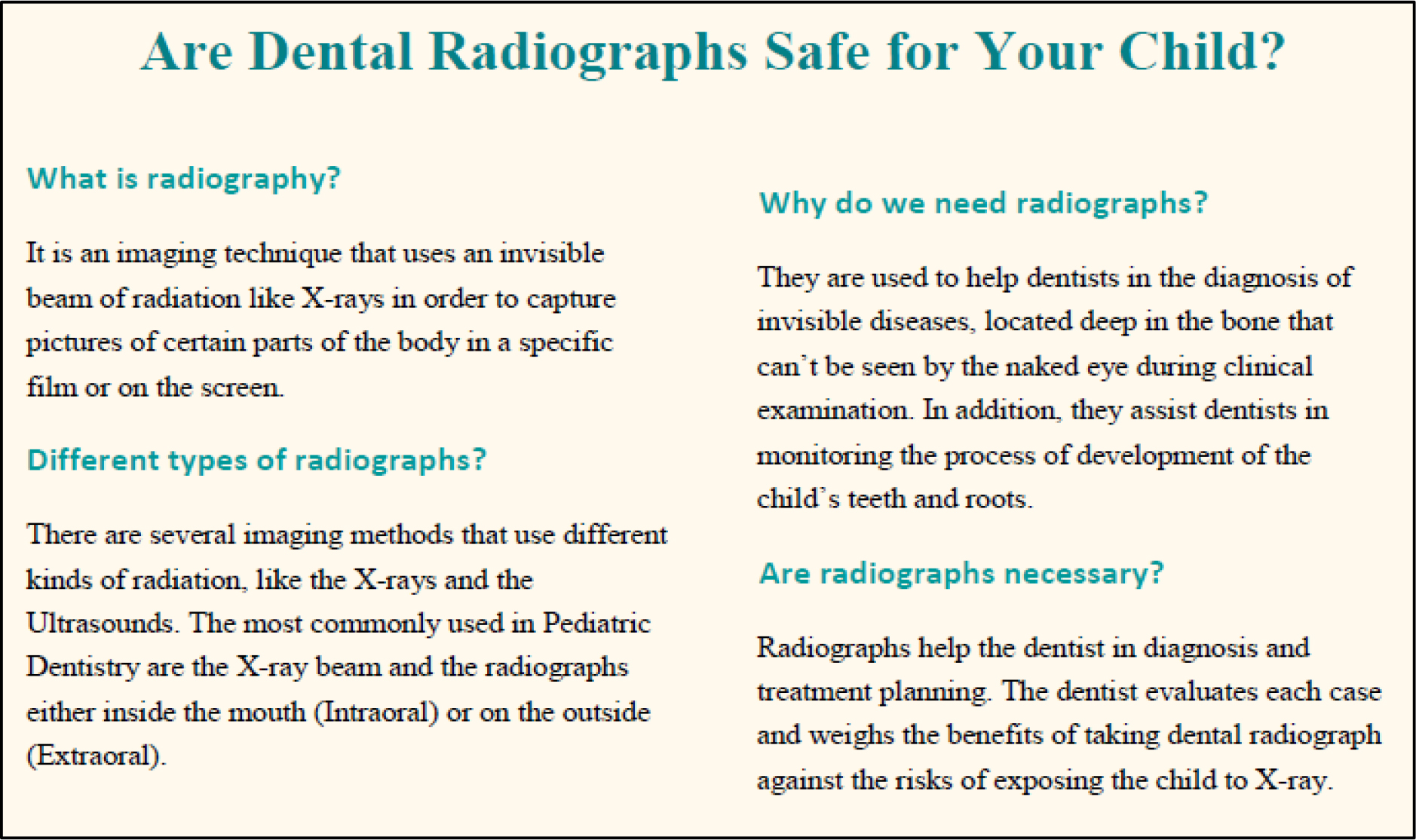

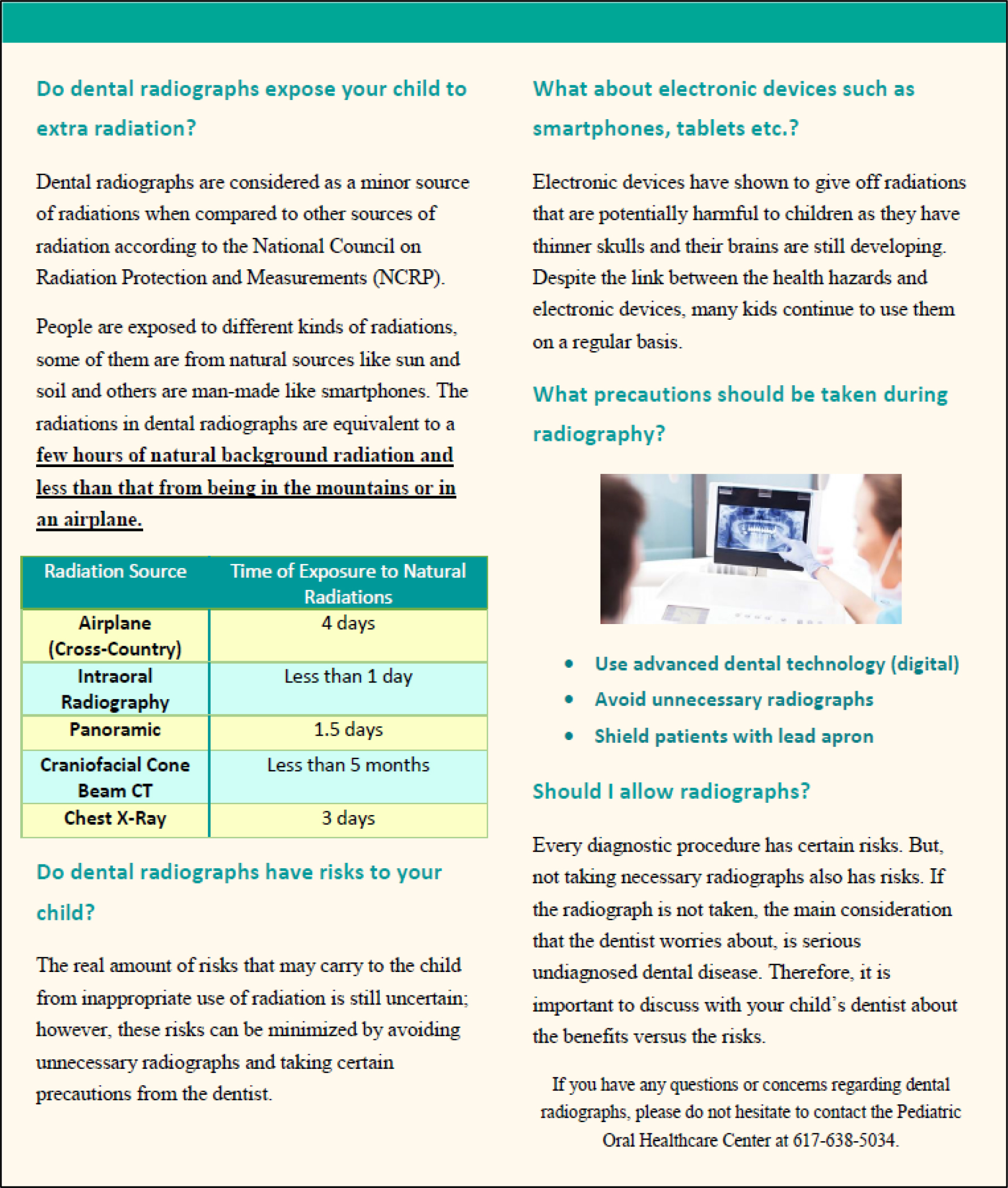

The materials utilized for the educational component in this study included a short two-sided informational handout titled ‘Are dental radiographs safe for your children?’ (S1a and S1b Figures), and a mobile application called ‘Medical Imaging Risk (MIR)’ (S2 and S3 Figures). The informational handout used in this study was in English language, easy to read and the content was prepared at the 8th grade level as is the standard when preparing patient related text (S1a and S1b Figures). Colorful images, text and tables were used to educate parents on dental radiography and provide information on sources of radiation and their different dose estimations highlighting the radiation dose with routine dental radiographs. The handout while emphasizing the benefits and importance of dental radiography in early diagnosis and treatment also outlined the possible risks from unnecessary imaging procedures.

S1a Figure. Information on side 1 of the printed handout:

S1b Figure. Information on side 2 of the printed handout:

S1 Figure. Printed two-sided informational handout used in the educational intervention.

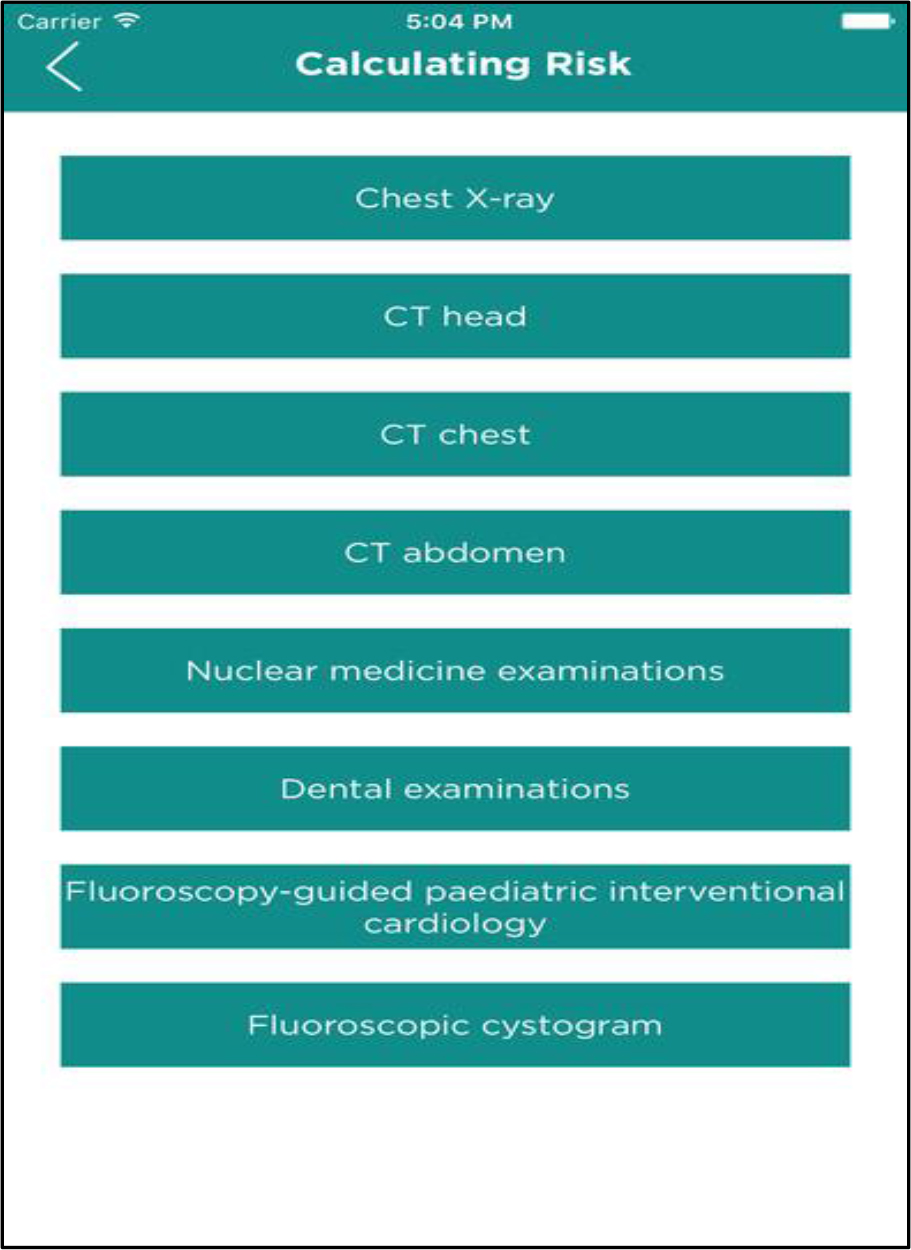

S2 Figure. Medical Imaging Risk (MIR) mobile application: Types of radiographic tests listed in the application.

S3 Figure. Medical Imaging Risk (MIR) mobile application: Types of dose equivalents for selected radiographic test by age.

Following the discussion using the informational handout, the mobile application (app), MIR was used to continue an interactive discussion on radiation imaging (S2 Figure). The use of the app was demonstrated, and participants were shown that this app can be easily downloaded for free on both the Android and Apple platforms. This user-friendly app provides information on the various dosages and risks by type of radiation imaging (S3 Figure). The app also provides additional resources for further detailed information that the participants can download for free.

Study Questionnaires

Two questionnaires, one immediately before (pre-intervention) and one immediately after (post-intervention) the educational intervention were used to obtain information on parents’ knowledge and perception towards pediatric imaging.

Pre-intervention questionnaire

In the pre-intervention questionnaire, which included 5 questions, parents responded if their child or children ever received dental imaging. Irrespective of their response to this question parents completed the remainder of the questionnaire. Parents responded to questions on the level of confidence in their knowledge on risks and benefits of radiation and were asked to choose from three options: Not confident, somewhat confident and very confident. To evaluate specific knowledge, parents were asked to respond to whether smartphones and electronic devices emitted harmful radiation to which they responded ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Participants also responded to their level of comfort in their child undergoing any type of radiation imaging by choosing from three options: Not comfortable, somewhat comfortable and very comfortable. Demographic information such as participants’ gender, race, ethnicity and insurance type were also obtained in the pre-intervention questionnaire to evaluate differences in parent responses.

Post-intervention questionnaire

The post-intervention questionnaire, which included 8 questions, included the same five questions that was in the pre-intervention questionnaire, to evaluate a change in perception or comfort if any as a result of the intervention. In addition, questions on whether the educational material discussed during the intervention improved their understanding about dental radiographs and if the participants continued to have concerns about them were also included and both of these questions generated a response of ‘yes’ versus ‘no’. One of the goals of the post-intervention questionnaire was also to explore the preferred method of communication when receiving health information during dental care visits and the participants chose between printed materials versus mobile application. This question was not included initially however it was added later during the study as our goal was also to collect data on the parent perspective related to the educational material. As a result not all of the participants responded to this question. The study application was amended with this additional question and IRB approval was obtained to make this change.

Statistical Analysis

Participants’ responses to the questionnaires, pre versus post intervention, were compared and analyzed using STATA version 14.0 statistical analysis software. Differences in knowledge and perception were also evaluated by demographic characteristics. Descriptive and univariate categorical data analysis was conducted to evaluate differences and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 213 parents participated in this study, reflecting the population base of the Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine. The majority were mothers (82.6%), having Medicaid as their primary dental insurance (81.7%). Also, most of the participants were African Americans, 54.9% followed by 17.8%n White; 7.04% Asian; and 16.4% self-identified as Hispanic/Latino (S1 Table).

Most of the participants in this study (75%) reported that their child/children have had previous dental radiographs (S1 Table). When comparing participants’ level of confidence on their knowledge towards benefits of dental radiographs for their children, 74% of participants reported either not confident or somewhat confident in the pre-intervention questionnaire. This trend changed in the post-intervention period as an improvement in the level of confidence was evident with 65% of the participants reporting that they are very confident. This improvement in the level of confidence was statistically significant with p<0.001 (S1 Table). Similarly, when evaluating the confidence level on the knowledge of risks of dental radiographs for their children, 69% of participants were either not confident or somewhat confident in the pre-intervention questionnaire. However, this trend also changed in the post-intervention period where 58% reported being very confident with statistically significant results (p<0.001).

S1 Table. Characteristics of the study participants (N = 213).

|

Characteristic |

n (%) |

|

Gender, n (%) |

|

|

Females |

176 (82.6%) |

|

Males |

37 (17.4%) |

|

Race/Ethnicity, n (%) |

|

|

Caucasian |

38 (17.8%) |

|

African American |

117 (54.9%) |

|

Hispanic/Latino |

35 (16.4%) |

|

Asian/Pacific Islander |

15 (7.04%) |

|

Other |

8 (3.8%) |

|

Type of insurance, n (%) |

|

|

MassHealth |

174 (81.7%) |

|

Other |

39 (18.3%) |

|

History of previous dental radiographs for participants’ child/children, n (%) |

|

|

Yes |

159 (74.7%) |

|

No |

54 (25.4%) |

In the pre-intervention, more than half the study population (59%) reported that they were either not comfortable or somewhat comfortable in allowing dental radiographs for their children (S2 Table). However following the educational intervention, in the post-intervention, a significant majority (66%) reported being very comfortable (p<0.001).

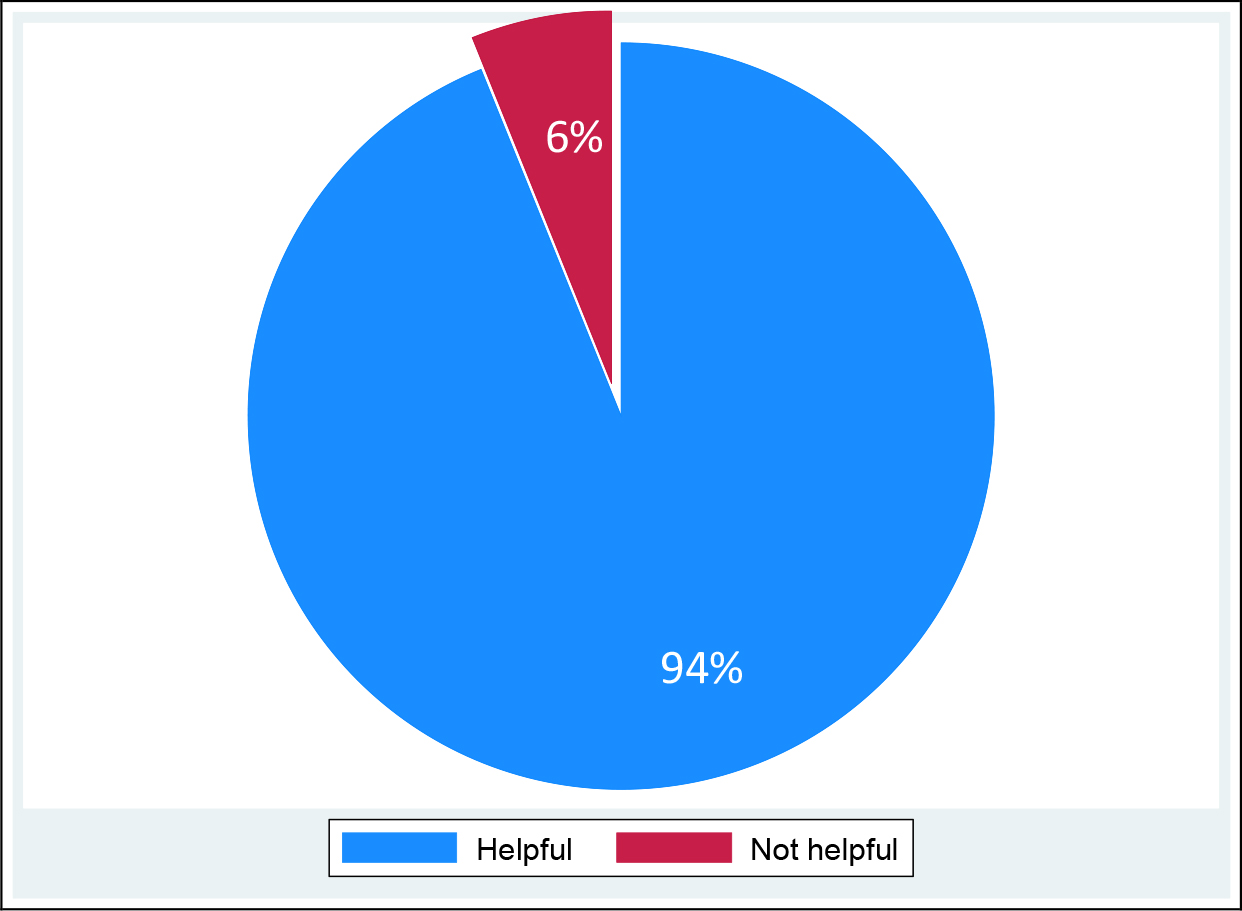

In the post-intervention analysis regarding the helpfulness of the educational materials, the great majority (94%) had a positive response (S4 Figure). Eighty two percent reported no concerns with dental radiographs after reviewing the materials during the educational intervention (S2 Table). When evaluating the preferred method of communication of health information, interestingly the responses were almost equally distributed. As mentioned previously, this question was initially not included in the post-intervention questionnaire and was added after our pilot exploration. Therefore, the complete sample population was not included in the comparison of preferred method of communication. Among 147 parents or caregivers 53% reported that they preferred the printed handout versus 47% reported that they preferred the mobile phone application (S5 Figure). No significant differences by gender, race/ethnicity and insurance type was observed as the majority of the participants in this study was women, African-American and had Medicaid insurance (S1 Table). Hence due to the lack of variability by demographic characteristics we did not observe statistically significant differences by these characteristics and were unable to explore potential confounding by these factors in multivariate analyses.

S4 Figure. Helpfulness of the educational materials in understanding of pediatric radiation imaging (post-intervention) N = 213.

S5 Figure. Preference for receiving health information (post-intervention) N= 147.

S2 Table. Evaluation of parental knowledge and attitudes of radiation imaging among pediatric caregivers at the Pediatric Oral Health Center (N = 213)

|

Radiation Imaging |

Pre-test questionnaire n (%) |

Post-test questionnaire n (%) |

p-value |

|

|

Level of confidence in knowledge about benefits |

||||

|

Not confident |

52 (24.4) |

2 (0.94) |

||

|

Somewhat confident |

105 (49.3) |

72 (33.8) |

||

|

Very confident |

56 (26.3) |

139 (65.3) |

<0.0001* |

|

|

Level of confidence in knowledge about risks |

||||

|

Not confident |

38 (17.8) |

9 (4.2) |

||

|

Somewhat confident |

109 (51.2) |

80 (37.6) |

||

|

Very confident |

66 (31.0) |

124 (58.2) |

<0.0001* |

|

|

Level of comfort in allowing the use of dental radiographs |

||||

|

Not comfortable |

28 (13.2) |

11 (5.2) |

||

|

Somewhat comfortable |

98 (46.0) |

61 (28.6) |

||

|

Very comfortable |

87 (40.8) |

141 (66.2) |

<0.0001* |

|

|

Reported understanding of radiation from electronic devices |

||||

|

Yes |

140 (65.7) |

162 (76.1) |

||

|

No |

73 (34.3) |

51 (23.9) |

<0.0001* |

|

|

Level of comfort in using dental radiographs by race/ethnicity before intervention |

Not comfortable |

Somewhat comfortable |

Very comfortable |

|

|

White |

7 (25) |

21 (21.4) |

10 (11.5) |

|

|

African-American |

15 (53.6) |

50 (51.0) |

52 (59.8) |

|

|

Hispanic/Latino |

6 (21.4) |

17 (17.4) |

12 (13.8) |

|

|

Pacific Islander |

0 (0) |

6 (6.1) |

9 (10.3) |

|

|

Other |

0 (0) |

4 (4.1) |

4 (4.6) |

0.29† |

|

Level of comfort in using dental radiographs by race/ethnicity after intervention |

||||

|

White |

3 (27.3) |

12 (19.7) |

23 (16.3) |

|

|

African-American |

5 (45.5) |

32 (52.5) |

80 (56.7) |

|

|

Hispanic/Latino |

2 (18.2) |

14 (22.9) |

19 (13.5) |

|

|

Pacific Islander |

1 (9.1) |

1 (1.6) |

13 (9.2) |

|

|

Other |

0 (0) |

2 (3.3) |

6 (4.3) |

0.47† |

|

Concerns regarding dental radiographs (post-intervention)‡ |

n (%) |

|||

|

Yes |

174 (81.7) |

|||

|

No |

39 (18.3) |

|||

*Results from Pearson Chi-square analysis.

†Based on results from Fisher’s Exact analysis;

‡Post-intervention question

Discussion

Overall the results from our study indicate that a simple brief educational intervention in the dental office can not only improve parental the level of knowledge but can also increase their level of confidence and comfort thus enabling them to be more accepting and comfortable with radiation imaging procedures for their child/children. Our study also explored the preferred mode of communication among parents and we observed that the majority preferred the printed informational handout over the mobile application.

Communication of health risks and benefits is an important step towards better provider-patient relationship. Particularly in pediatric dentistry the level of anxiety among children and their parents are high due to mainly lack of knowledge among patients and parents, which may be as a result of failing to receive adequate information prior to dental procedures. While dental providers showed an acceptable level of knowledge on radiation risks, evidence from one study reported that the patients’ knowledge was inadequate [17]. Similar findings were reported in another study conducted in Australia where among 309 parents there was a low level of knowledge [18]. In our study, in the pre-intervention questionnaire, parents reported a lower level of confidence in knowledge of risks and benefits of radiation however this significantly improved in the post-intervention following the educational intervention and discussion using the mobile application. This was also observed in the previously mentioned study in Australia where the investigators reported that parents with higher level of education appeared to have not only higher knowledge of radiation risks but were more likely to accept radiation imaging as ‘safe’ and ‘beneficial’. A study in Malaysia among patients reported that insufficient knowledge was associated with higher level of disapproval of the use of dental imaging among children [13]. In our study in the post-intervention when parents were asked if they still had concerns and if they comfortable in allowing their children to undergo imaging procedures, the majority reported that they did not have concerns and that they were very comfortable.

The risk-benefit dialogue is an important component of patient care in the current practice of dentistry and can aid in lowering the level of fear anxiety towards radiation [3,19]. This dialogue should be designed based on individual patient needs. The providers should also keep in mind that each patient and family differ in terms of their social and cultural background, medical and dental history, and access to care, especially given the growing diversity of the demographics in the US [20]. The risk communication strategy should be developed keeping in mind the prominent role of the parents in clinical decision making of dental treatment for their children. Dental practitioners should be aware that parents’ risk perception is often influenced by social factors, personal belief systems, previous health experiences, socio-economic factors and level of education [20]. Therefore, when communicating health information it is vital that dental practitioners take these factors into account and communicate information to the parents and children in a way that is easy for them to comprehend. In our study as we did not collect information on level of education and socio-economic factors. We collected information on insurance type which can be a proxy for economic level however the majority of the participants in our study since the majority reported Medicaid as their insurance we were unable to evaluate differences by economic level of the participants. The demographic characteristics observed in our study are however reflective of the patient population at the Boston University’s Goldman School of Dental Medicine.

Our educational intervention used a brief two-sided printed informational handout and a mobile application. The informational handout included content in simple easy to understand 8th grade level of English language as is the standard when preparing consent forms in English. The mobile application MIR, which was used in our study intervention was also simple user-friendly application. The preference for material used in health communication was distributed almost equally with slightly higher preference for the printed handout. This clearly points to the need to have various types of parental educational aids available in the dental clinic as individuals tend to have diverse learning styles and preferences. A recent study collected data on patient perspectives on how physicians should communicate information on radiation risks to patients and the results suggest that there was equal preference for both oral and written information [19]. Previous studies that used multi-media educational materials for dental procedures have reported successful improvement in knowledge [21,22]. Another study reported that text-messaging was more effective than printed pamphlets when educating mothers. These methods of communicating health information should also be considered for future long-term studies.

Graphic display and visually appealing text play an important role in enhancing health communication and improving knowledge [1]. Our educational handout with information on radiation risks and benefits was colorful with visual images and tables with clear breakdown of details on radiation dosages. As a result, the parents in our study may have preferred the printed handout a little more than the mobile application for the ease of information description and availability of the handout on hand. However, almost half the population preferred the mobile application MIR which may have been for those who prefer the portability and availability of information in their personal devices.

Limitations of our study include the short follow-up time following the intervention as the post-intervention questionnaire was handed out to the parents immediately after the intervention. Parents’ knowledge of risks and benefits may be higher as a result of this short follow-up time. Future studies should consider a longer follow-up period to evaluate long term retention of knowledge. Also, in our study while we described the availability of the mobile application MIR, there is no information about whether parents who preferred the use of the app downloaded the app and whether they continued to use it. Again, a study with longer follow-up period will be able to determine the frequency of use and the long-term benefits of the mobile application.

According to the policy statement published by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), in the field of medical practice, key elements in improving physician-parent-child communications are (adapted from Levetown MaCob 2008 AAP policy statement) [24]:

- Informativeness: Quantity and quality of health information provided by physicians.

- Interpersonal sensitivity: Behavior of the physician that reflects his or her attention to or interest in parents’ and child’ feelings or concerns.

- Partnership building: Extent to which the physician opens a dialogue that allows the parents or children to share their perspectives and suggestions.

These concepts can be applied in the field of dentistry as well to improve dentist-parent-child communications which in turn will improve the overall treatment and management thus resulting in improved oral and systemic health of the child. In our study we demonstrated that even a simple brief educational intervention during a child’s dental care visit can significantly improve the level of comfort and confidence among parents and caregivers. Future research can utilize our study model to design larger studies with longer follow-up and more detailed information on patient and parent background. This can lead to better understanding on parental and patient preferences and perspectives that will in turn help practitioners to design more effective health communication strategies.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the parents who participated in this study.

References

- Dauer L, Thornton R, Hay J, Balter R, et al. (2011) Fears, feelings, and facts: Interactively communicating benefits and risks of medical radiation with patients. American Journal of Roentgenology 196: 756–61.

- Thornton R, Dauer L, Shuk E, Bylund C, et al. (2015) Patient perspectives and preferences for communication of medical imaging risks in a cancer care setting. Radiology 275: 545–52.

- WHO, World Health Organization (2015) Communicating radiation risks in paediatric imaging: Information to support healthcare discussions about benefit and risk. Geneva 2016.

- Madan K, Baliga S, Thosar N, Rathi N (2015) Recent advances in dental radiography for pediatric patients. Journal of Medicine, Radiology, Pathology & Surgery 1: 21–5.

- Linton O, Mettler Jr. F (2003) National council on radiation protection and measurements. In National conference on dose reduction in CT, with an emphasis on pediatric patients. American Journal of Roentgenology 181: 321–9.

- White S, Scarfe W, Schulze R, Lurie A, et al. (2014) The Image Gently in Dentistry Campaign: promotion of responsible use of maxillofacial radiology in dentistry for children. Journal of Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology 118: 257–61.

- ADA, American Dental Association: Image Gently Alliance. [Internet]. 2007 [cited August 26, 2019]. Available from: https://www.imagegently.org/About-Us/The-Alliance.

- Aanenson J, Till J, Grogan H (2018) Understanding and communicating radiation dose and risk from cone beam computed tomography in dentistry. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 120: 353–60.

- Brody A, Frush D, Huda W, Brent R (2007) Radiation risk to children from computed tomography. Pediatrics 120: 677–82.

- Chiri R, Awan S, Archibald S, Abbott P (2013) Parental knowledge and attitudes towards dental radiography for children. Australian Dental Journal 58: 163–9.

- Lee C, Haims A, Monico E, Brink J, Forman H (2004) Assessment of patient, physician, and radiologist awareness of radiation dose and possible risks. Radiology 231: 393–8.

- Ludwig R, Turner L (2002) Effective patient education in medical imaging: public perceptions of radiation exposure. Journal of Allied Health 31: 159–64.

- Purmal K, Alam M, Nambiar P (2013) Patients’ perception on dental radiographs. International Medical Journal 20: 235–8.

- Friedberg W, Copeland K, Duke F, O’Brien III K, Darden Jr. E (2000) Radiation exposure during air travel: guidance provided by the Federal Aviation Administration for air carrier crews. Health Physics 79: 591–5.

- Hwang H. Knowledge, attitude and perception on radiation imaging among children’s caregivers in pediatric dental clinic.: Boston University; 2017.

- Zavras J, Hwang H, Murray G, Zletni A, Shanmugham J (2018) Educational intervention to increase parental knowledge and acceptance of pediatric imaging. Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Care 8: 1–7.

- Aravind B, Joy E, Kiran M, Shrubin J, et al. Attitude and awareness of general dental practitioners toward radiation hazards and safety. Journal of Pharmacy and Bioallied Sciences. 2016;8(1):553–8.

- Chiri R, Awan S, Archibald S, Abbott P (2013) Parental knowledge and attitudes towards dental radiography for children. Australian Dental Journal 58: 163–9.

- Lumbreras B, Vilar J, Gonzalez-Alvarez I, Guilabert M, et al. (2017) Avoiding fears and promoting shared decision-making: How should physicians inform patients about radiation exposure from imaging tests? PLoS One 12: 1–14.

- Garcia R, Cadoret C, Henshaw M (2008) Multicultural issues in oral health. Dental Clinics of North America 52.

- Pei D, Liang B, Du W, Wang P, et al. (2017) Multimedia patient education to assist oral impression taking during dental treatment: A pilot study. International Journal of Medical Informatics 102: 150–5.

- Kazancioglu H-O, Dahhan A-S, Acar A-H (2017) How could multimedia information about dental implant surgery effects patients’ anxiety level? Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal 22: 102–7.

- Sharma R, Hebbal M, Ankola A, Murugabupathy V (2011) Mobile phone text messaging (SMS) for providing oral health education to mothers of preschool children in Belgaum city. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 17: 432–6.

- Levetown MaCoB (2008) Communicating with children and families: From everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. American Association of Pediatrics 2008.