Abstract

Background – Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and fatty liver disease are considered to be off-shoots of insulin resistance. However, the link between the two disorders have recently been found to be variable.

Objective – To explore the association of fatty liver disease with PCOS and to model the association of hyperandrogenism, obesity and insulin resistance indices among subjects with or without PCOS and fatty liver disease.

Methodology – This study was carried out between Jan-2018 to Aug-2019 at PNS HAFEEZ hospital. Odds ratio (OR) for having PCOS with fatty liver disease were calculated. We utilized general linear model (GLM) by keeping hyperandrogenism, abdominal volume index (AVI) and insulin resistance as dependent variables against PCOS and fatty liver disease as independent factors.

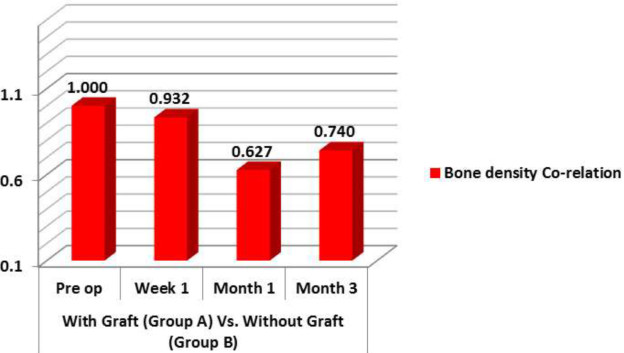

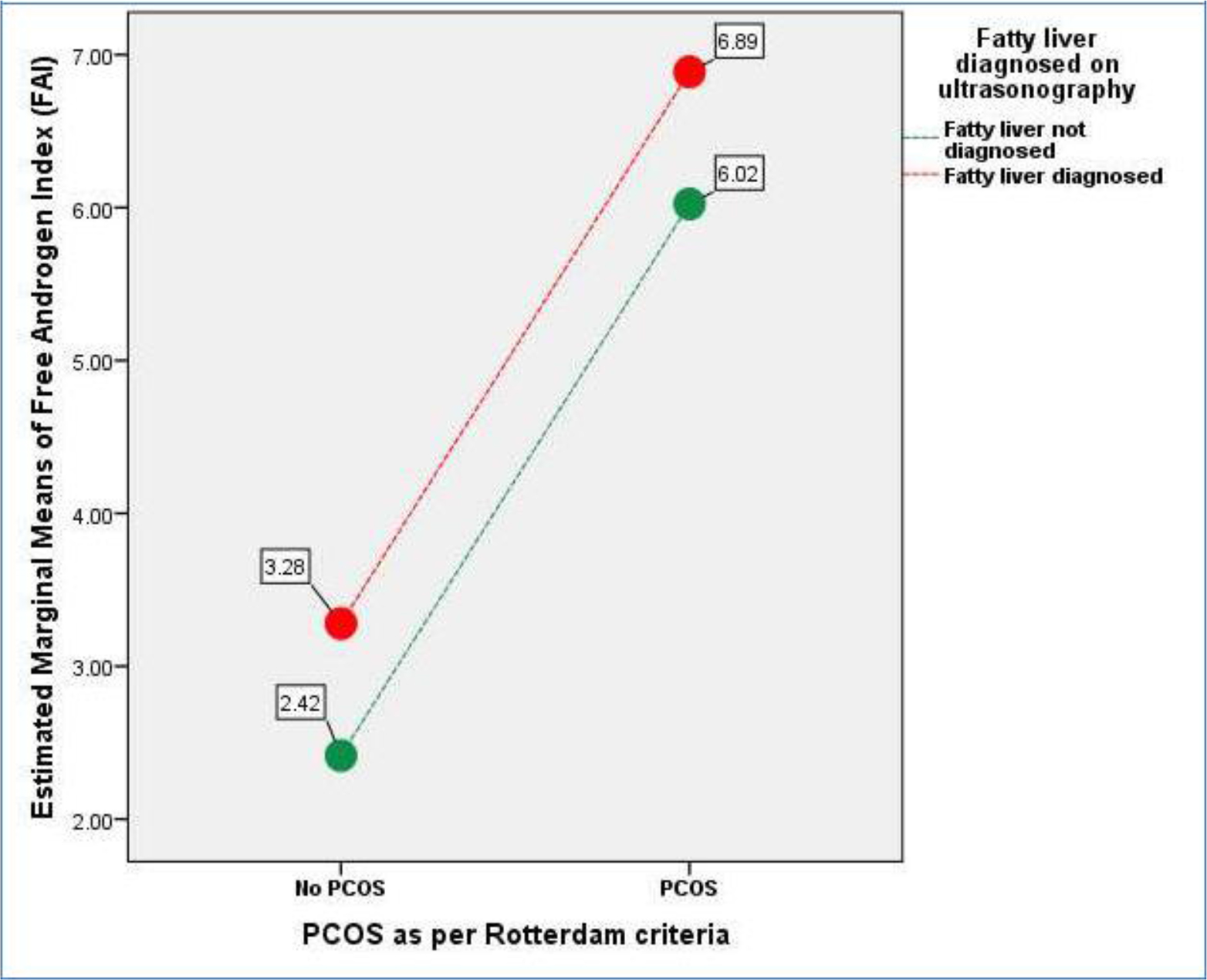

Results – OR for having PCOS in subjects with fatty liver disease was 1.34(95%CI: 1.34(0.868-2.065). Using Free Androgen Index(FAI) as dependent variable and fatty liver and PCOS as fixed factors in a GLM analysis, the group wise differences are depicted as: Group-1: No Fatty liver+No PCOS=2.37(+1.30),n=97), Group-2: No PCOS+Fatty Liver=3.35(+2.23),n=66), Group-3: PCOS+No Fatty Liver=6.08(+5.05),n=88), and Group-4: PCOS+Fatty Liver=6.83(+4.70),n=80).(p<0.001). Abdominal obesity was not associated with PCOS (p=0.980), but was significantly associated with fatty liver disease (p<0.001).

Conclusion – Presence of fatty liver disease in females can lead to slightly higher frequency of PCOS. Biochemical and clinical hyperandrogenism were associated with presence of PCOS, while abdominal obesity and insulin resistance were linked with fatty liver disease.

Keywords

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), free androgen index (FAI), modified Ferriman-Gallwey score (mFG score), fatty liver and Rotterdam PCOS criteria.

Background

Lipids are considered as the mainstream culprits in pathogenesis of development of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and fatty liver disease. [1, 2] Therefore the probability based upon the famous “Common Soil Hypothesis” dealing in directly with metabolic syndrome suggest a common linkage between the two pathogenic disorders. [3] Both PCOS and Fatty liver disease amounts to multiple complications. PCOS has been shown to result in hirsutism and reproductive issues. [4], while fatty liver disease is associated with acceleration liver damage leading to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). [5]

While the mechanism seems more understandable in terms of extra fat accumulation within liver but some evidence indicates PCOS phenotype variability does allow differential association with fatty liver disease. Macut et al have shown that subjects having higher serum testosterone, a hallmark of PCOS are associated with a two-fold increased risk of fatty liver. [6] Rocha et al in their systematic review from 2007 to 2017 highlighted that prevalence of PCOS with NAFLD remains variable, but the combined presence of PCOS and NAFLD results in higher degree of clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism than the female subjects only demonstrating PCOS with former category more associated with metabolic derangements. [7] Contrary to that there is evidence where both fatty liver disease and PCOS are associated and attributed to common pathogenesis. The research work by Vassilatou et al have demonstrated that lipid based abnormalities are central to the development of PCOS and NAFLD; however, he categorized data from PCOS patients as either being obese or otherwise. [8] Similarly, Kauffman et al have demonstrated that PCOS and NAFLD can occur due to common pathogenic mechanisms including androgen excess and insulin resistance. [9, 2]

So, the obvious question arises as to how fat accumulation or associated metabolic defects differentially affect the two organs? While PubMed data search indicates both fatty liver disease /NASH/NAFLD and PCOS both being the off-shoots of insulin resistance, [10] still there are both genetic and epigenetic mechanism at work which can probably change the overall phenotype of metabolic syndrome and related diseases. In this regard a study from Poland had identified GG genotype variation to result in higher frequency of NAFLD in PCOS than PCOS subjects without Cannabinoid Receptor-1 gene polymorphism thus highlighting genetic predilections towards PCOS-fatty liver occurrence. [11] Similarly, Jones et al have identified higher risk of fatty liver disease with hyperandrogenism associated PCOS in comparison to female subjects having reduced hyperandrogenism independent of insulin resistance. [12] Bruce et al by highlighting the concept of “Metabolic Circadian Clock System” have attempted to highlight epigenetic factor from environmental triggers which change the phenotypic presentation of metabolic syndrome, and thus can be interpreted indirectly as the effect of regional effects or ethnic triggers. [13] Another aspect of this is the adipocyte size which has been shown to result in variability in hepatic steatosis [14], which have been smaller but with increase adipocyte area in Asian population than Caucasians and so the affect could be due to specific racial reasons [15]. So racial differences due to variability adipocyte area, genetic factors and epigenetic influences need to be considered and may probably be different in whatever has been observed elsewhere. Based upon these newly emerging evidence a compelling need was therefore felt to learn the association between the PCOS, fatty liver disease and androgenicity which were supposedly to be associated due to common trigger i.e., insulin resistance.

A study is therefore planned to explore the association of fatty liver disease, PCOS and hyperandrogenism by estimating the hirsutism, anthropometric, biochemical and endocrine differences (Free androgen index) between subjects with fatty liver associated PCOS and non-fatty liver PCOS.

Methods

We planned a cross-sectional analysis among reproductive-age female subjects after formal approval of hospital’s ethical review committee of PNS HAFEEZ Hospital. The study involved department of radiology, pathology, obstetrics and gynecology. The duration of study was 18 months from Jan-2018 to Aug-2019. Females in reproductive age post 2 years of menarche were initially included as target population. Patient selection was based non-probability convenience mode of sampling. Females who some acute or chronic conditions including pelvic inflammatory disease, metabolic diseases like hypertension, diabetes and ischemic heart disease, autoimmune disorder, on any medication, fertility treatment, or other unknown drugs were excluded from the study. Subjects who could not complete all testing formalities for any reason were excluded from the study. Finally selected females were formally requested to visit pathology department on 2nd day of menstrual cycle Subjects who finally followed up for study in medical fasting were formally

explained about study design, requirements and were asked to sign a consent form. Further clinical evaluation included history, evaluation of hirsutism as per modified Ferriman-Gallwey scores [16], anthropometric measurements, vital signs measurements and a generalized clinical examination for any signs of chronic disease. They were questioned about duration of menstrual cycle for presence or absence of oligo/anovulation as per criteria utilized by Kollmann et al. [17]

Radiological and laboratory analysis: 10 ml (approx.) of blood was collected for fasting plasma glucose, ALT, HbA1c, total testosterone, Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) and serum insulin and lipid profile. Following sample collection, females were requested to go for radiological examination for evaluation of reproductive tract examination for presence or absence of polycystic ovarian syndrome as per Rotterdam criteria [18]

Lab analysis and measurements: Fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol and triglycerides were measured on Selctra-ProM (Clinical chemistry analyzer) by GPO-PAP, CHOD-PAP and GPO-PAP method. LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol were measured by direct enzymatic methods using accelerator selective detergent on Selectra-proM. ALT was measured by IFCC method at 370C. Total testosterone, SHBG, glycated hemoglobin were analyzed by using chemiluminescent microparticle Immunoassay (CMIA) on ARCHITECT (iSystem) developed by Abbot Diagnostics. Serum insulin was measured on Chemiluminescence method on Immulite® 1000 analyzer. Internal and National External Quality Assurance Program are in place to monitor inter and intra lab imprecision along with internal QC management for precision and accuracy by documented trouble shooting on instrument generated charts as per Westgards’s standard protocols.

Calculated parameters – Free Androgen Index (FAI) was measured as: FAI = (Total testosterone/SHBG) x 100. FAI > 5%was greater than 5% was termed as biochemical hyperandrogenism as per Al Kindi et al. [19] Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin resistance (HOMAIR) was measured using Mathew’s et al mathematical model. [20]

Data analysis – We used SPSS-version 24 for statistical analysis. Age was calculated as per mean and SD by descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics for frequency of PCOS, hirsutism and fatty liver disease % were calculated for subjects with or without fatty liver disease. Inferential statistics involved calculation of Odds Ratio for presence of PCOS as per Rotterdam criteria in subjects with or without fatty liver disease. We utilized General linear models (GLM) where we evaluated sequentially FAI, mFG scores for hirsutism, abdominal volume index (AVI) and insulin resistance (HOMAIR) as dependent variables against presence or absence of PCOS and fatty liver disease as fixed factors.

Results

Mean age among subjects with Rotterdam defined PCOS was (26.71+ 6.99, n=168) and without PCOS was (29.07+ 8.11, n=163). Similarly subjects who had fatty liver had a mean age of (30.95+7.10, n=146) in comparison to females without fatty liver [25.45+7.17, n=185). 236 females in our data set were married, while 95 were non-married. Hirsutism was diagnosed in 157 females while 174 were having a modified FG score of less than 8. 88/185 (47.57%) of the cases without fatty liver disease were diagnosed with PCOS, while 80/146 (54.79%) of cases diagnosed to have fatty liver disease had PCOS indicating no statistically significant association between presence of PCOS and fatty liver disease in our regional data set. Odds ratio (OR) for having PCOS in subjects with fatty liver disease is 1.34 but not statistically significant. (Table-1)

Table 1. Odds ratio for presence of PCOS as per Rotterdam criteria in subjects with fatty liver disease (p=NS).

|

|

|

|

PCOS

|

|

|

Odds Ratio

|

|

|

|

|

(Rotterdam criteria)

|

|

|

(95 % CI)

|

|

|

|

|

NO

|

|

YES

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fatty liver diagnosed

|

Fatty liver not

|

97

|

|

88

|

185

|

|

|

|

|

on ultrasonography

|

diagnosed

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.34

|

|

|

|

Fatty liver

|

66

|

|

80

|

146

|

|

(0.868-2.065)

|

|

|

|

diagnosed

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

|

163

|

|

168

|

331

|

|

|

|

Keeping free androgen index (FAI) as dependent variable with PCOS and fatty liver disease as fixed variables indicates a definite increase in FAI due to presence of PCOS which get slightly worsened with the presence of fatty liver depicted as: Group-1: No Fatty liver + No PCOS= 2.37 (+ 1.30), n=97), Group-2: No PCOS + Fatty Liver = 3.35(+

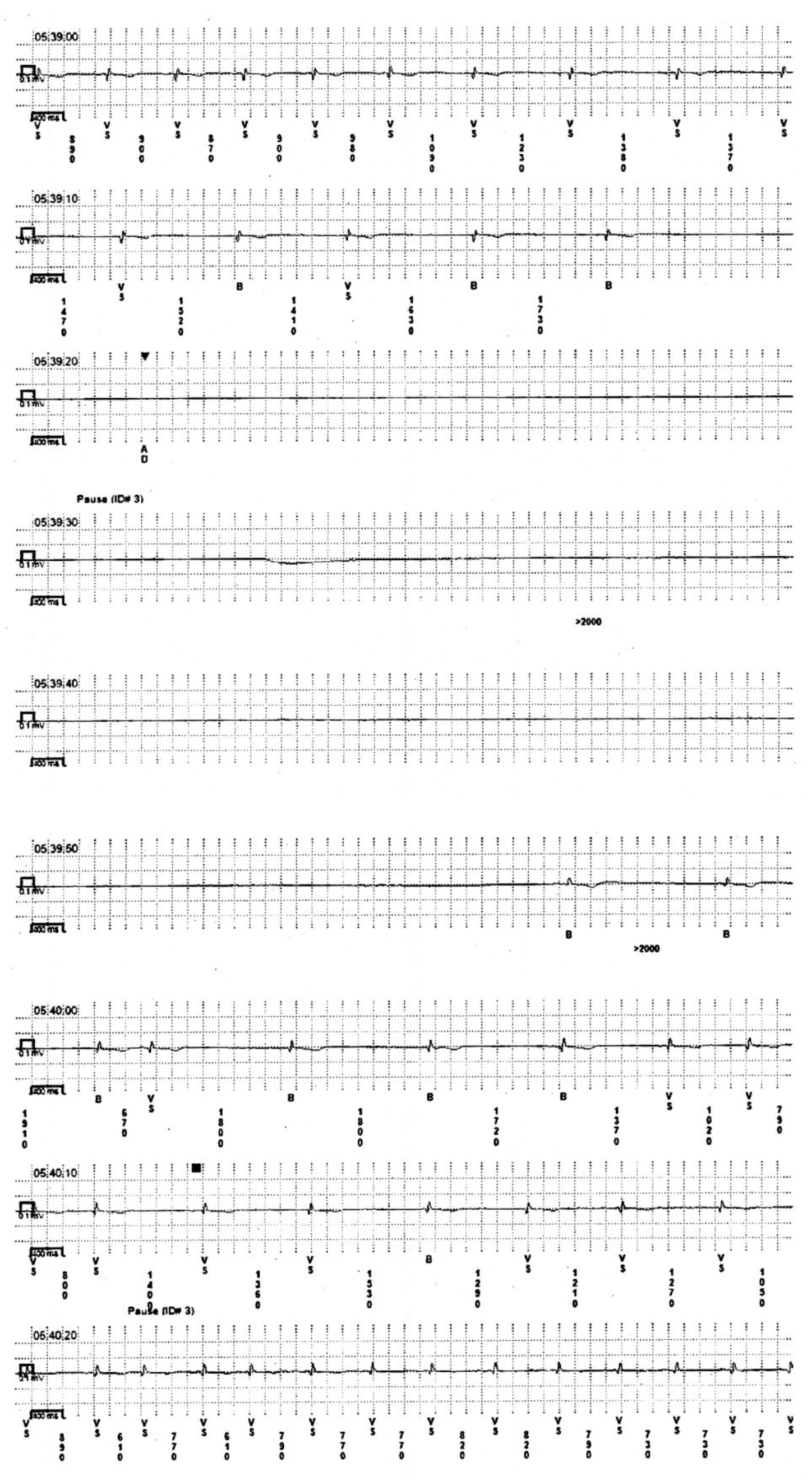

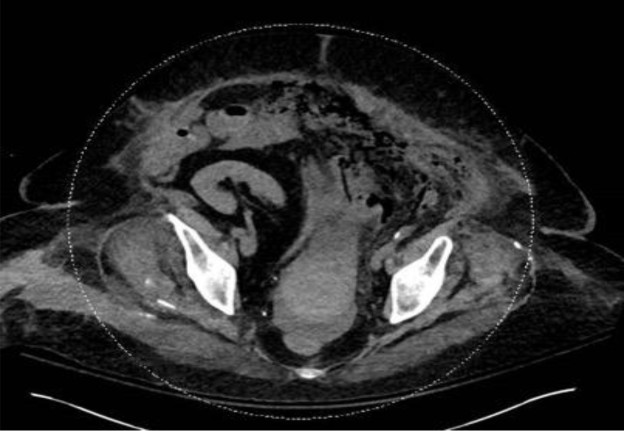

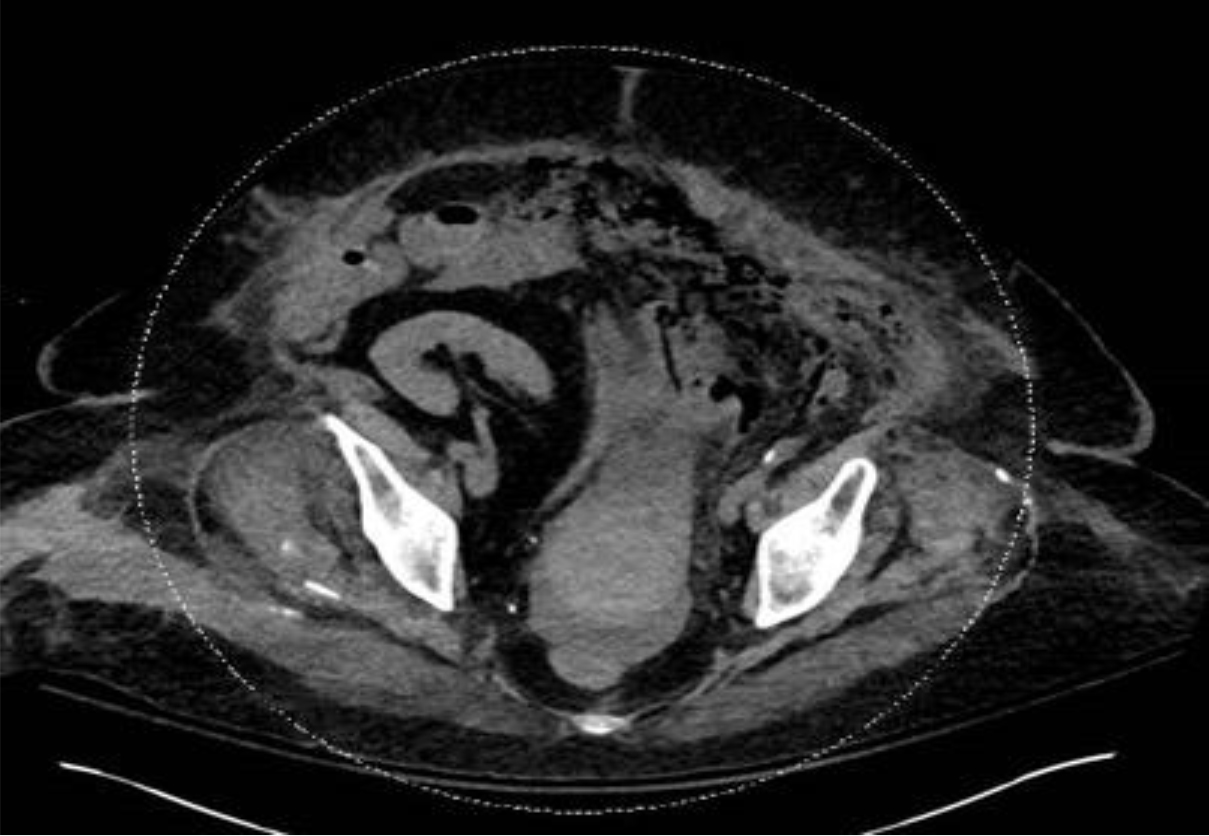

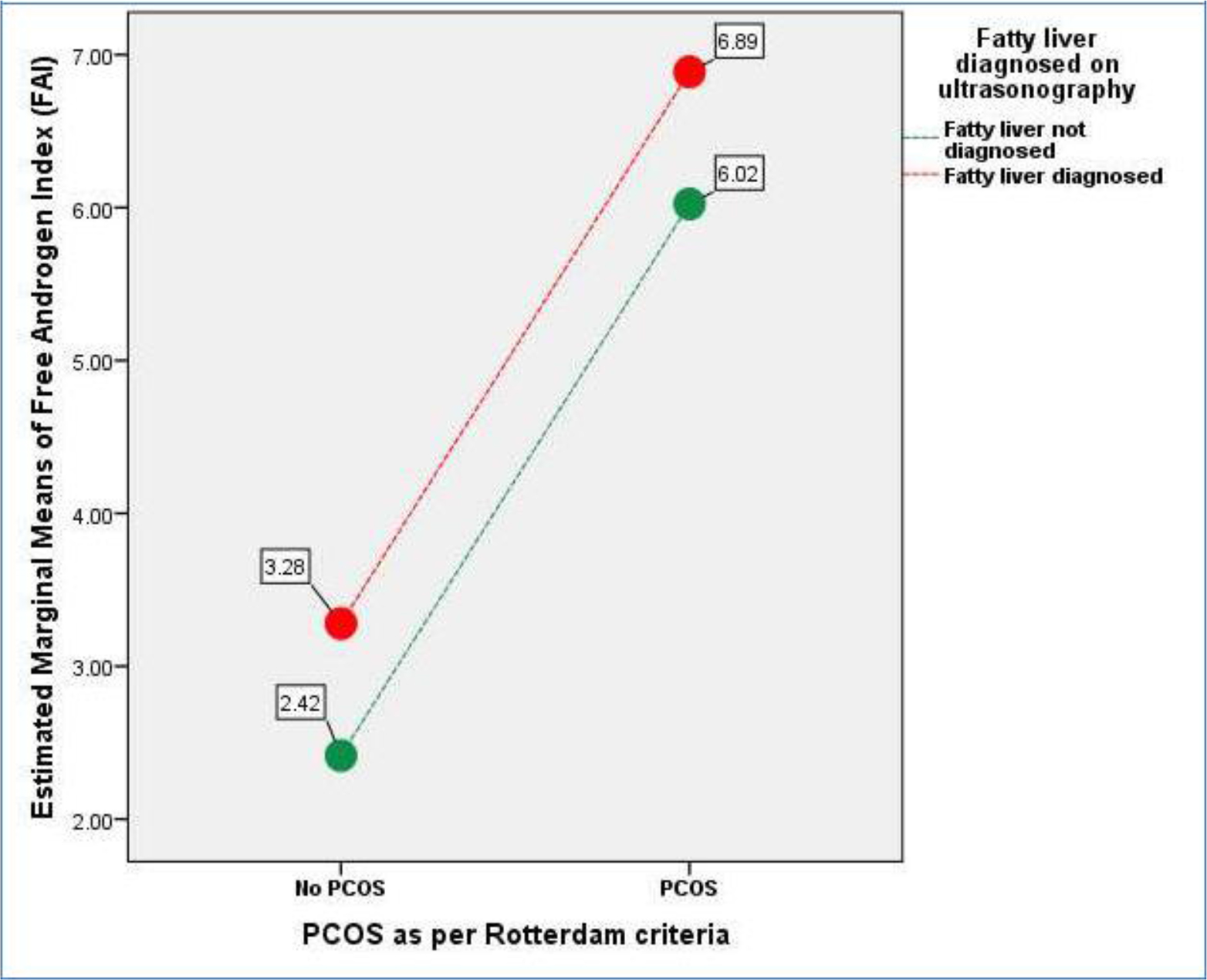

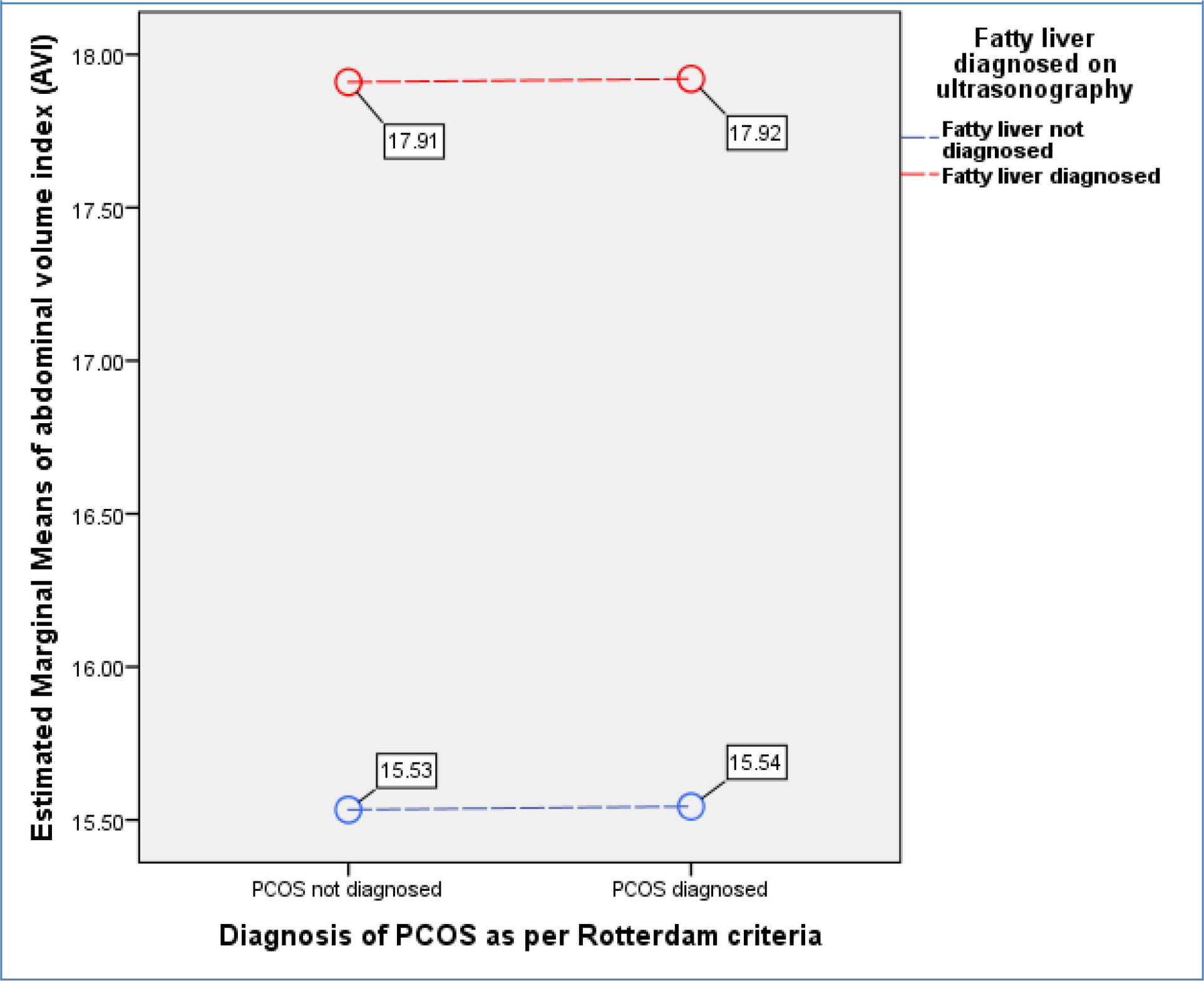

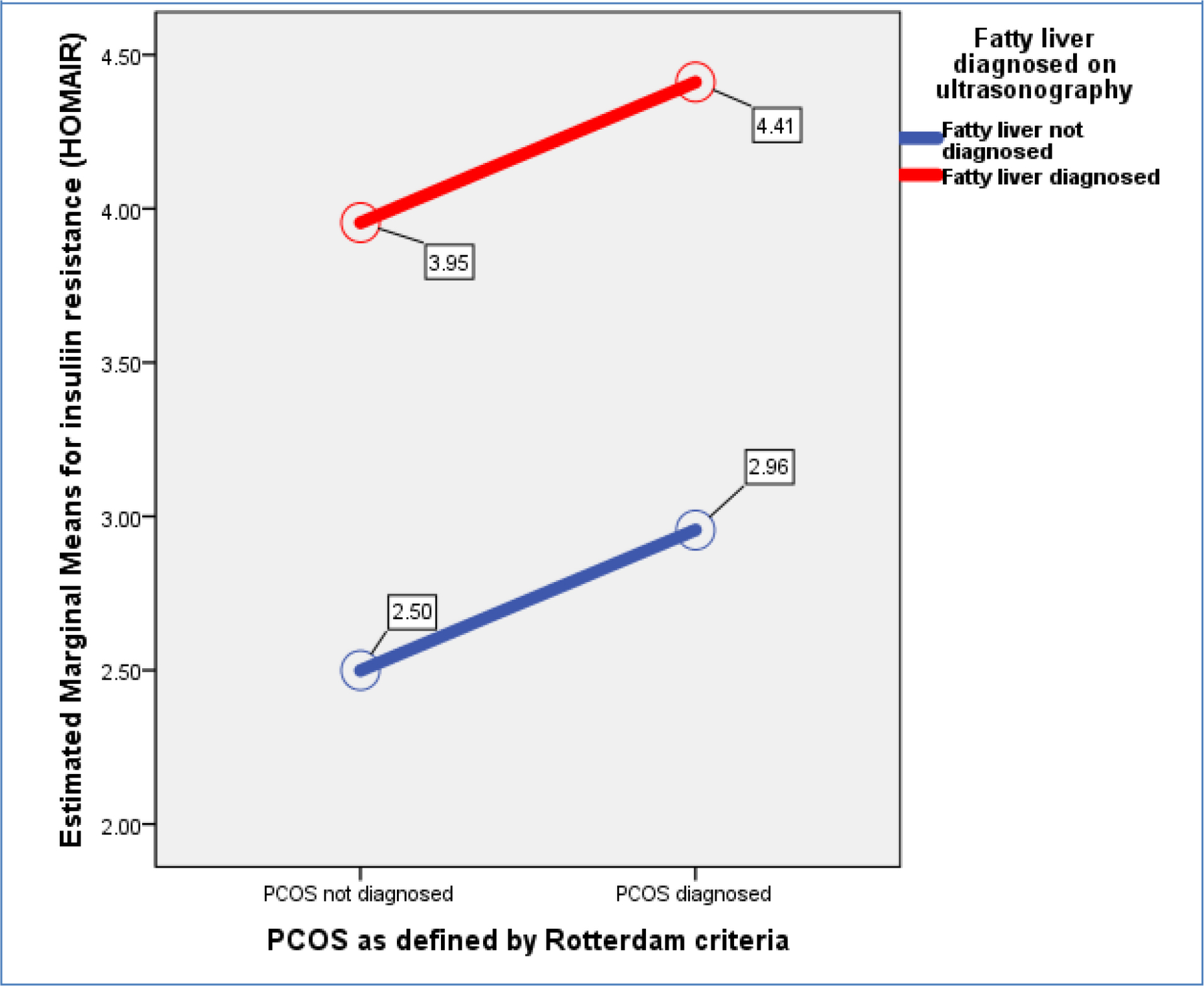

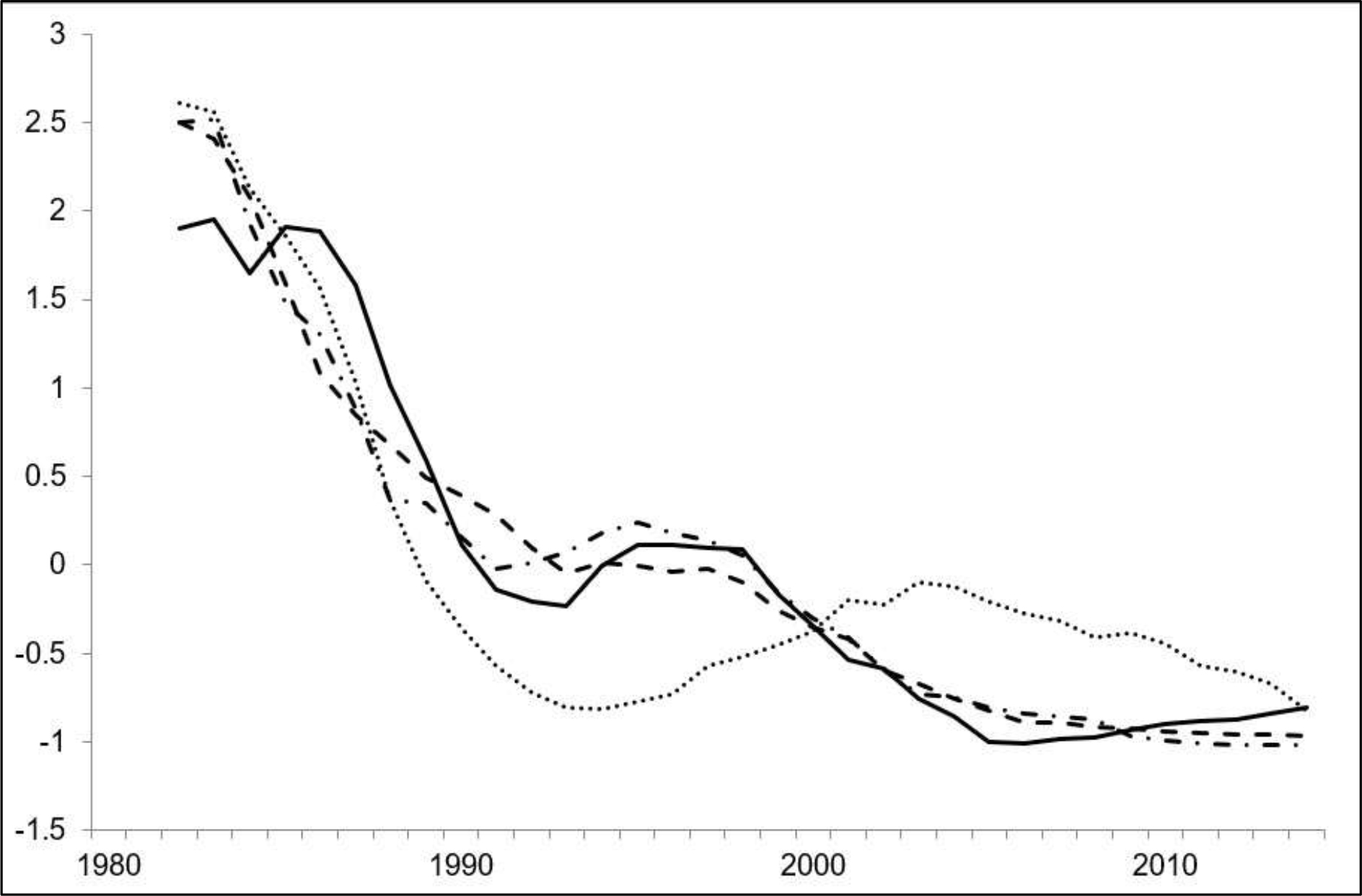

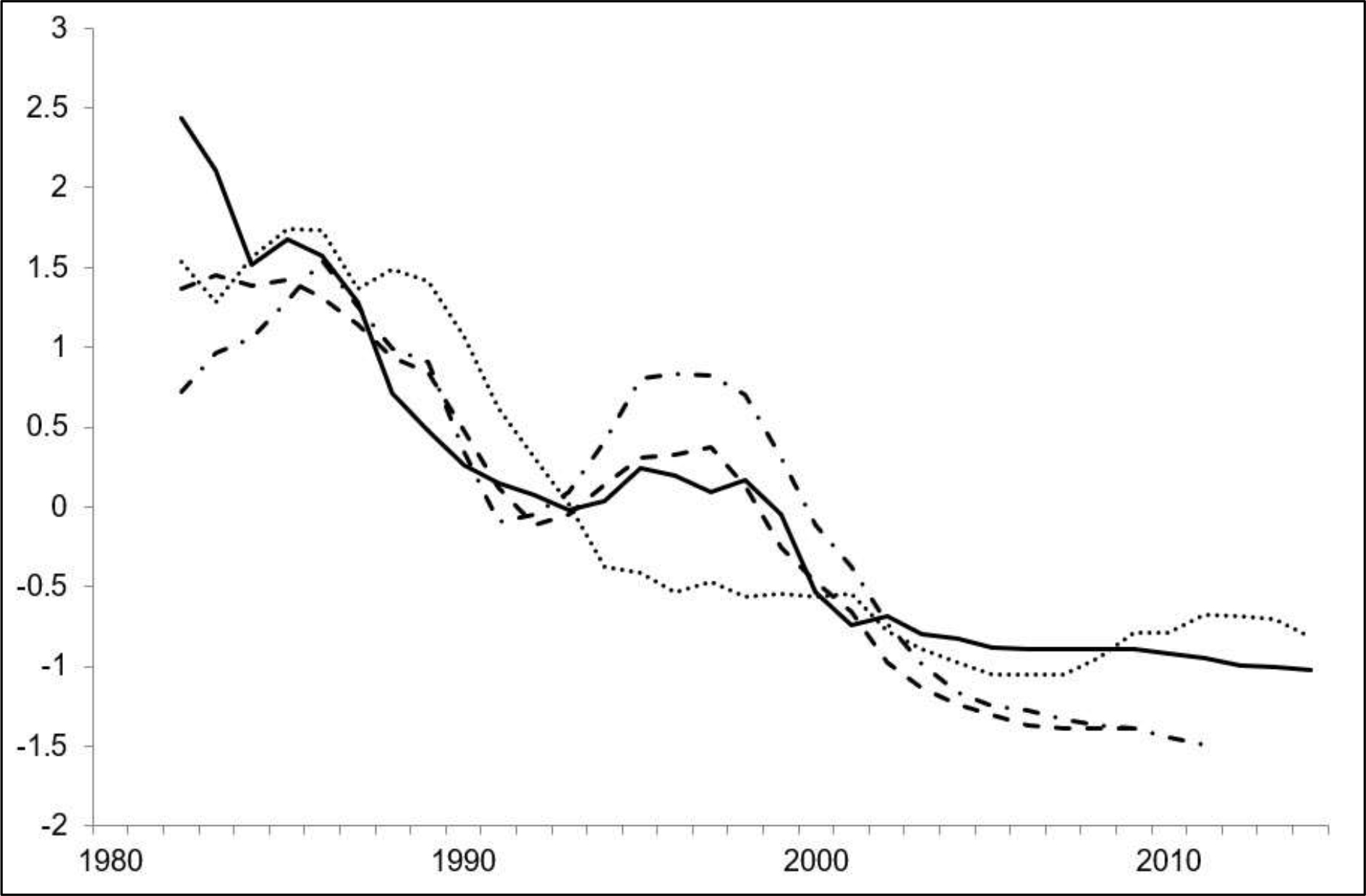

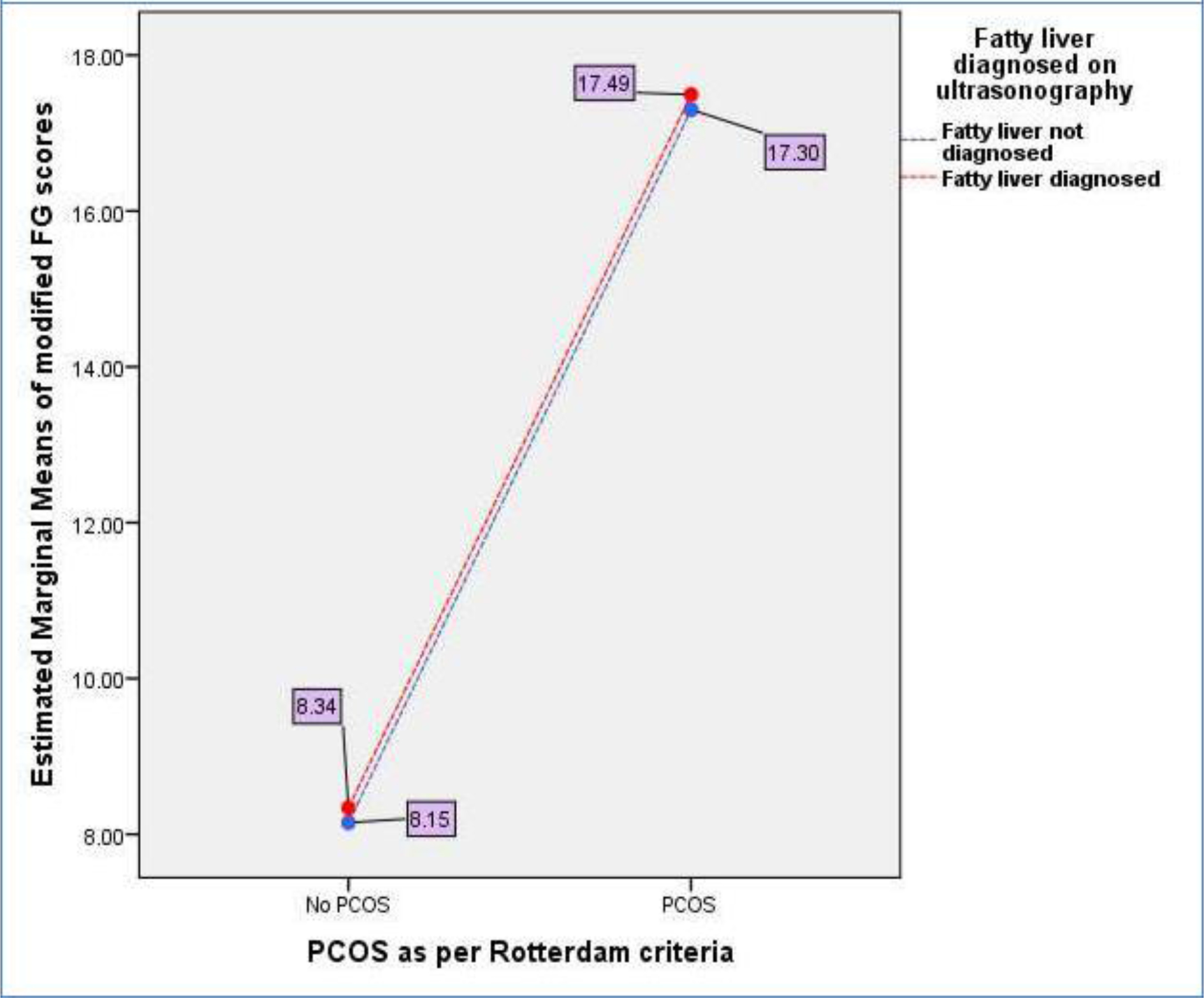

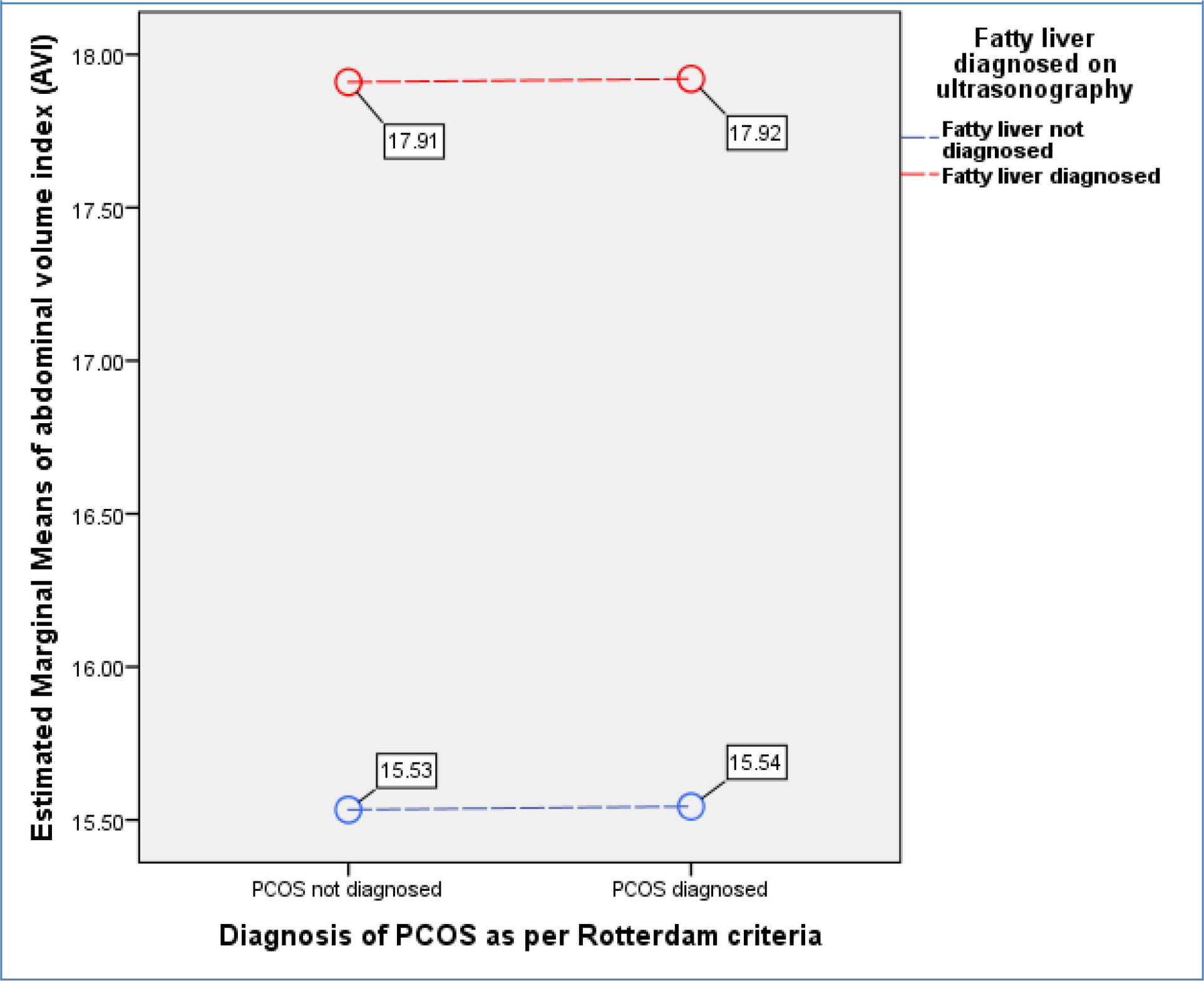

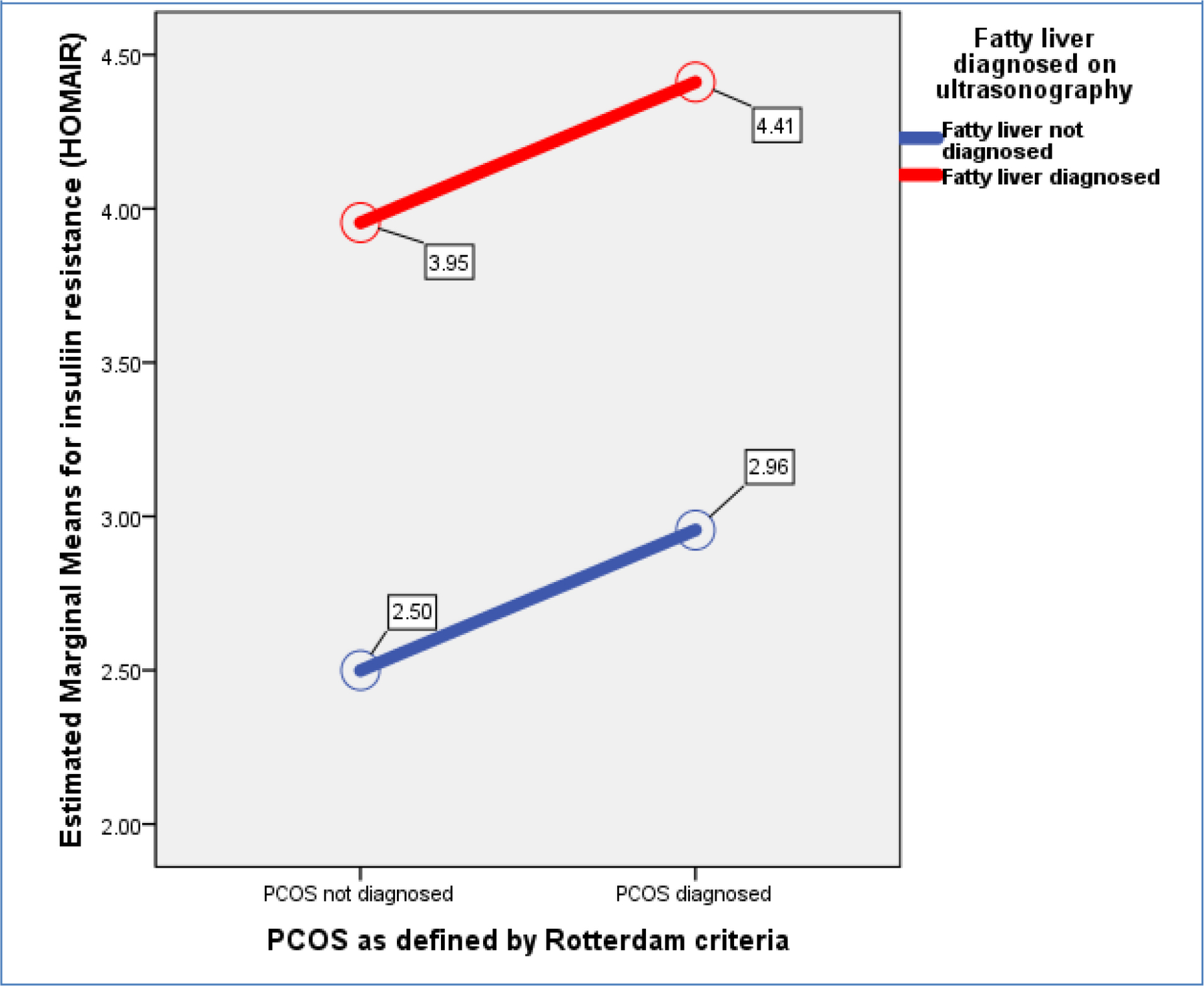

2.23), n=66), Group-3: PCOS + No Fatty Liver = 6.08 (+ 5.05), n=88), and Group-4: PCOS + Fatty Liver = 6.83 (+ 4.70), n=80). Figure-1 shows a General Linear Model (GLM) with FAI being a dependent variable is evaluated against independent variables i.e., presence or absence of PCOS (p<0.001) and fatty liver disease (p=0.035) demonstrating that PCOS presence is more associated with increase in biochemical hyperandrogenism than fatty liver disease. (Overall Model significance<0.001). Similarly, hirsutism as measured by mFG scores was not significantly related to fatty liver disease but was associated with presence of PCOS. [Figure-2] Abdominal Volume Index (AVI) as a measure of abdominal obesity was not associated with PCOS, but was significantly associated with fatty liver disease. [Figure-3] Furthermore, insulin resistance as a dependent variable was seen to rise more with the presence of fatty liver in comparison to PCOS. [Figure-4]

Figure 1. General Linear Model (GLM) where FAI being a dependent variable is evaluated against independent variables i.e., presence or absence of PCOS (p<0.001) and fatty liver disease (p=0.035). (Overall Model significance<0.001).

Figure 2. General Linear Model (GLM) where mFG score as surrogate markers for hirsutism being a dependent variable is evaluated against independent variables i.e., presence or absence of PCOS(p <0.001) and fatty liver disease(p=0.820). (Overall Model significance<0.001).

Figure 3. General Linear Model (GLM) where Abdominal Volume Index (AVI) as a marker for abdominal obesity being a dependent variable is evaluated against independent variables i.e., presence or absence of PCOS (p=0.980) and fatty liver disease (p<0.001). (Overall Model significance<0.001).

Figure 4. General Linear Model (GLM) with insulin resistance as dependent variable and presence or absence of PCOS (p=0.157) and fatty liver disease (p<0.001) as independent variables (Overall Model significance<0.001).

Discussion

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and fatty co-occurrence in study subjects was slightly higher than subjects with having one of the pathology, implying a very weak association between the two entities. Though the OR for presence of PCOS in subjects with fatty liver disease was above i.e., 1.34 but it was not statistically significant. Our data identified free androgen index and hirsutism to be more associated than fat deposition within liver as factors in contributing polycystic ovarian pathology. Furthermore we identified increase in AVI i.e., as a surrogate for abdominal fat deposition and insulin resistance to be more associated with presence of fatty liver disease than with PCOS. The trend, hence identified a strong link for insulin resistance in causation of fatty liver disease and hyperandrogenism for PCOS. Contrary to our findings the data from some studies have highlighted a stronger link between obesity an insulin resistance markers with as common culprits in associating fatty liver and PCOS. [7, 8, 10, 11].

Macut et al have also identified a much higher combination diagnosis of PCOS and fatty liver disease than presence of a single pathology in Serbian population. [21] Coming to our data in terms of finding a weaker link it is important to understand that lean PCOS types are well-recognized in sub-continental population. [22] More so as Pande et al evaluated obesity and insulin resistance indices in these lean category of PCOS and observe them to be dissimilar than obese PCOS subjects, where the latter group were found to have more metabolic derangements.

[23] Similar to that Chinese have results quite similar to ours, where BMI and NAFLD were minimally associated with PCOS females. [24] Even some European studies have found a higher percentage of up to 40% lean-PCOS in their studies. [25] However, if we study the western population a contrast appear where insulin resistance and higher trunk fat mass clearly supersedes the Asian PCOS phenotype. [26] Therefore regional differences and possible epigenetic triggers can be attributed to the differential or minimal relationship between fatty liver disease and insulin resistance in subjects with PCOS.

Possible understanding of authors on this minimally existent relationship between PCOS and fatty liver disease in our data subjects is being explained below: Firstly, we described in the introduction that adipocyte size variation between Asian and Caucasian population, so possibly smaller adipocyte among Asians with capacity to accumulate more fat led to lesser abdominal volume indices and fatty liver disease in our data of female subjects. [15, 24] The argument therefore can be made that these most often obese-PCOS phenotypes females had higher insulin resistance due to increase fat mass and least contributed by hyperandrogenism. [26] However, we as author feel more interventional trials can clarify the real causation of PCOS and in specific its relation with abdominal and hepatic steatosis. Secondly, what impact the weather, environment and lifestyle could lead to aforementioned variation of PCOS patterns? We highlighted earlier the findings of

Bruce et al who described the role of environment in causing variable PCOS phenotypes. [13] A Spanish study by Concha et al evaluated the epigenetic marks by analyzing miRNAs and histone methylation in various body fluids and tissues to conclude a very strong impact of environmental triggers in association

with development of PCOS. [27] Pursuant and related directly to epigenetic mechanisms Monniaux et al was able to demonstrate in ovine fetuses that over exposure of follicular and uterine tissues may lay the foundation stone for a possible PCOS phenotype. [28] Finally, dietary patterns may be a significant contributor to PCOS as studies on gut microbiome had a different phylogenetic type along with lower density than control female subjects. [29] Thus shifting diet patterns from traditional and more natural food consumption to refined and high caloric diets could be an add on, if not causative factor in leading to PCOS development. We, therefore believe with globalization and mixing of people and in specific adopting western style diets and life styles the disease pattern may change overtime tilting more in favor of obese-phenotype. [30]

Certain limitations regarding our cross-sectional analysis needs to be taken into account: Firstly, we did this study in hospital-setting and our findings must be extrapolated to an epidemiological level to understand PCOS and its phenotype prevalence within our community. Secondly, we feel certain cultural barriers persist in our community due to lack of basic medical education and history. Provided our questionnaire format was structured and no language barrier was there still we interpret and this aspect to cause some degree of bias.

This study has important clinical implication especially in backdrop of wide regional and racial variation PCOS phenotypes. Taken the study setting and cross-sectional design the study can be further replicated to validate phenotypes of PCOS prevailing at broader level. Thus more data should follow this study project. However, this article does provide a broader guideline in terms of interpreting and segregating PCOS phenotypes within our population, which can help treating physicians to specify their treatment options in a more personalized manner. On a national scale the data also highlights the need for local guidelines for our community using this data and evidence from surrounding regions.

Conclusion

Presence of fatty liver disease in females can lead to slightly higher frequency of PCOS. Biochemical and clinical hyperandrogenism were more associated with presence of PCOS than with fatty liver disease, while abdominal obesity and insulin resistance were more often than not associated with fatty liver disease in comparison to PCOS.

Declarations

- The data sets and SPSS outputs used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on formal request.

- Ethical approval – The study “Relationship between polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and fatty liver disease” was approved by ethical committee of the hospital. All participants were volunteer and provided “written consent” for the study.

- Author’s contributions – SHK: (Author for all Correspondence) Study plan, Involved in study plan, involved in sampling, methodology, lab analysis, data analysis, manuscript writing. SA: History collection, data analysis, and contributed towards discussion. RS: Radiological diagnosis of PCOS, Defining PCOS as per criteria, manuscript writing. RM: Initial patient history collection and examination, defining oligo/anovulation, data analysis, manuscript writing. RA: Patient examination, history writing, anthropometric measurements, manuscript writing. TC: Study plan, methodology, manuscript writing. Final manuscript was approved by all authors.

- Consent for publication: Signed consent was sorted from all study participants.

- Competing interests – There are no competing interests to declare.

- Data funding – The study had no funding source to disclose.

- Acknowledgements – The authors acknowledge the work of Miss Huma, and Lab technician Ibrahim and Iftikhar for the support.

Abbreviations

Fatty liver disease, Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), Free Androgen Index (FAI), Homeostasis Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMAIR), Modified Ferrimen Gellwey (mFG) score, Abdominal Volume Index (AVI).

References

- Tsouma I, Kouskouni E, Demeridou S, Boutsikou M, Hassiakos D and Chasiakou A. Lipid lipoprotein profile alterations in Greek infertile women with polycystic ovaries: influence of adipocytokines levels. In Vivo. 2014 Sep-Oct; 28(5): 935-9.

- Zhang X, Wang Y and Liu P. Omic studies reveal the pathogenic lipid droplet proteins in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Protein Cell. 2017 Jan; 8(1): 4-13. DOI: 10.1007/s13238-016-0327-9.

- Donati MB. The “common soil hypothesis”: evidence from population studies? Thromb Res. 2010 Apr; 125 Suppl 2: S92-5. DOI: 10.1016/S0049-3848(10)70023-2.

- Spritzer PM, Barone CR and Oliveira FB. Hirsutism in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Management. Curr Pharm Des. 2016; 22(36): 5603-5613.

- Margini C and Dufour JF. The story of HCC in NAFLD: from epidemiology, across pathogenesis, to prevention and treatment. Liver Int. 2016 Mar; 36(3): 317-24. DOI: 10.1111/liv.13031.

- Macut D, Bjekić-Macut J, Livadas S, Stanojlović O, Hrnčić D and Rašić-Marković A, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Curr Pharm Des. 2018; 24(38): 4593-4597. DOI: 10.2174/1381612825666190117100751.

- Rocha ALL, Faria LC, Guimarães TCM, Moreira GV, Cândido AL, Couto CA and Reis FM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017 Dec; 40(12): 1279-1288. DOI: 10.1007/s40618-017-0708-9.

- Vassilatou E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and polycystic ovary syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul 14; 20(26): 8351-63. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8351.

- Kauffman RP, Baker TE, Baker V, Kauffman MM and Castracane VD. Endocrine factors associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: do androgens play a role? Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010 Jan; 26(1): 39-46. DOI: 10.3109/09513590903184084.

- Baranova A, Tran TP, Birerdinc A and Younossi ZM. Systematic review: association of polycystic ovary syndrome with metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Apr; 33(7): 801-14. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04579.x.

- Kuliczkowska Plaksej J, Laczmanski L, Milewicz A, Lenarcik-Kabza A, Trzmiel-Bira A and Zaleska-Dorobisz U. Cannabinoid receptor 1 gene polymorphisms and nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and in healthy controls. Int J Endocrinol. 2014; 2014: 232975. DOI: 10.1155/2014/232975.

- Jones H, Sprung VS, Pugh CJ, Daousi C, Irwin A and Aziz N. Polycystic ovary syndrome with hyperandrogenism is characterized by an increased risk of hepatic steatosis compared to nonhyperandrogenic PCOS phenotypes and healthy controls, independent of obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Oct; 97(10): 3709-16. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2012-1382.

- Bruce KD and Cagampang FR. Epigenetic priming of the metabolic syndrome. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2011 May; 21(4): 353-61. DOI: 10.3109/15376516.2011.559370.

- Petäjä EM, Sevastianova K, Hakkarainen A, Orho-Melander M, Lundbom N and Yki-Järvinen H. Adipocyte size is associated with NAFLD independent of obesity, fat distribution, and PNPLA3 genotype. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013 Jun; 21(6): 1174-9. DOI: 10.1002/oby.20114.

- Anand SS, Tarnopolsky MA, Rashid S, Schulze KM, Desai D and Mente A. Adipocyte hypertrophy, fatty liver and metabolic risk factors in South Asians: the Molecular Study of Health and Risk in Ethnic Groups (mol-SHARE). PLoS One. 2011; 6(7): e22112. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022112.

- Goodman N, Bledsoe M, Cobin R, Futterweit W, Goldzieher J, Petak S, Smith K and Steinberger E: “American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Hyperandrogenism Guidelines”. Endocrine Practice 2001; 7(2): 120–13.

- Kollmann M, Klaritsch P, Martins WP, Guenther F, Schneider V and Herzog SA. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with PCOS: comparison of different diagnostic definitions. Hum Reprod. 2015 Oct; 30(10): 2396-403. DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dev187.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group 2004 Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 81: 19–25.

- Al Kindi MK, Al Essry FS, Al Essry FS and Mula-Abed WA. Validity of serum testosterone, free androgen index, and calculated free testosterone in women with suspected hyperandrogenism. Oman Med J. 2012 Nov; 27(6): 471-4. DOI: 10.5001/omj.2012.112.

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF and Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985 Jul; 28(7): 412-9.

- Macut D, Tziomalos K, Božić-Antić I, Bjekić-Macut J, Katsikis I and Papadakis E. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with insulin resistance and lipid accumulation product in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2016 Jun; 31(6): 1347-53. DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dew076.

- Goyal M and Dawood AS. Debates Regarding Lean Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Narrative Review. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017 Jul-Sep; 10(3): 154-161. DOI: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_77_17.

- Pande AR, Guleria AK, Singh SD, Shukla M and Dabadghao P. β cell function and insulin resistance in lean cases with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017 Nov; 33(11): 877-881. DOI: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1342165.

- Qu Z, Zhu Y, Jiang J, Shi Y and Chen Z. The clinical characteristics and etiological study of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese women with PCOS. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013 Sep; 11(9): 725-32.

- Ciotta L, Pagano I, Stracquadanio M and Formuso C. Polycystic ovarian syndrome incidence in young women with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Minerva Ginecol. 2011 Oct; 63(5): 429-37.

- Glintborg D, Petersen MH, Ravn P, Hermann AP and Andersen M. Comparison of regional fat mass measurement by whole body DXA scans and anthropometric measures to predict insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and controls. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016 Nov; 95(11): 1235-1243. DOI: 10.1111/aogs.12964.

- Concha C F, Sir P T, Recabarren SE and Pérez B F. Epigenetics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Rev Med Chil. 2017 Jul; 145(7): 907-915. DOI: 10.4067/s0034-98872017000700907.

- Monniaux D, Genêt C, Maillard V, Jarrier P, Adriaensen H and Hennequet-Antier C. Prenatal programming by testosterone of follicular theca cell functions in ovary. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019 Jul 20. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-019-03230-1.

- Lindheim L, Bashir M, Münzker J, Trummer C, Zachhuber V and Leber B. Alterations in Gut Microbiome Composition and Barrier Function Are Associated with Reproductive and Metabolic Defects in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Pilot Study. PLoS One. 2017 Jan 3; 12(1): e0168390. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168390. ECollection 2017.

- Rodgers RJ, Suturina L, Lizneva D, Davies MJ, Hummitzsch K, Irving-Rodgers HF and Robertson SA. Is polycystic ovary syndrome a 20th Century phenomenon? Med Hypotheses. 2019 Mar; 124: 31-34. DOI: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.01.019.